The Practice of Everyday Life

Richard Hawkins, Rebecca Watson Horn, Brook Hsu, Hanna Hur, Stanislava Kovalcikova, Maggie Lee, Kern Samuel, Naoki Sutter-Shudo, Tabboo!, Isadora Vogt, Ann Zhao

June 30–August 5, 2022

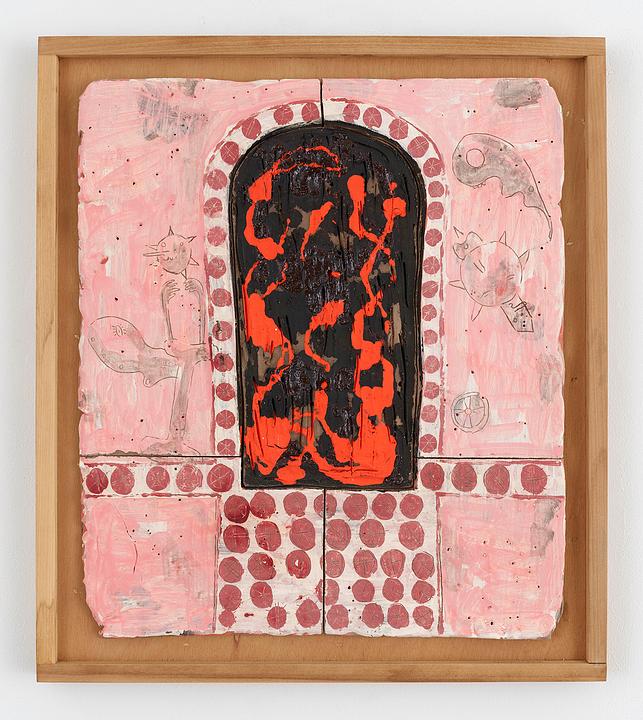

Richard Hawkins

Norogachian Consecration of Shit and Peyote, 2016

Glazed ceramic in artist's frame

25.75 x 22.75 x 1.625 in (65.4 x 57.8 x 4.1 cm)

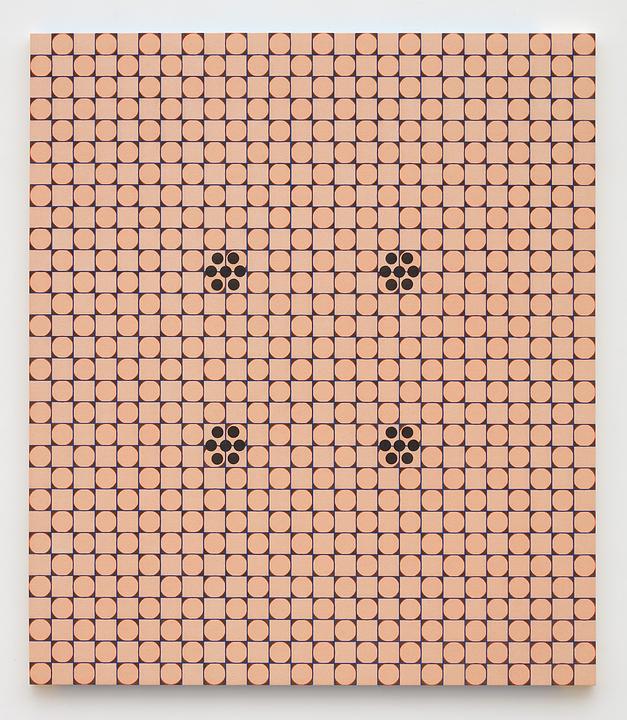

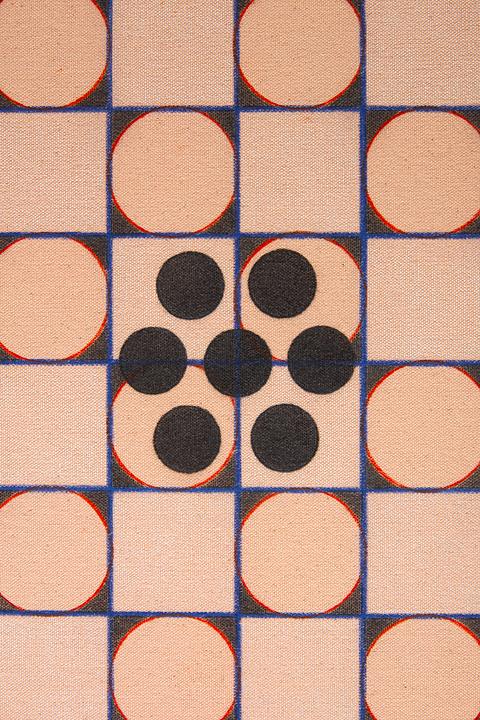

Hanna Hur

Quad vi, 2022

Acrylic and color pencil on canvas over panel

60 x 52 in (152.4 x 132.1 cm)

Isadora Vogt

Schweine, 2021

Pencil, chalk, acrylic on canvas

35.43 x 35.43 in (90 x 90 cm)

Brook Hsu

A Wanderer Plays on Muted Strings, 2022

Ink on canvas

78.75 x 70.85 in (200 x 180 cm)

Tabboo!

The Clock, 2018

Acrylic and glitter on linen

60 x 60 in (152.4 x 152.4 cm)

Naoki Sutter-Shudo

Grove, 2021

Wood, dye, enamel, flowers, stainless steel

11.25 x 26 x 9.5 in (28.6 x 66 x 24.1 cm)

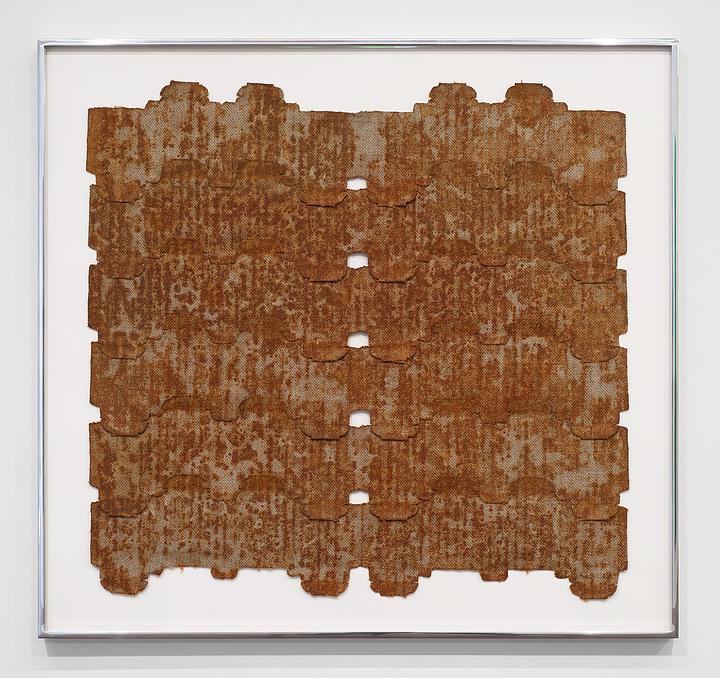

Kern Samuel

Old tin roof, 2022

Rust on linen

27 x 25 in (68.6 x 63.5 cm)

Kern Samuel

A good rain is coming, 2022

Acrylic on sewn canvas

27 x 25 in (68.6 x 63.5 cm)

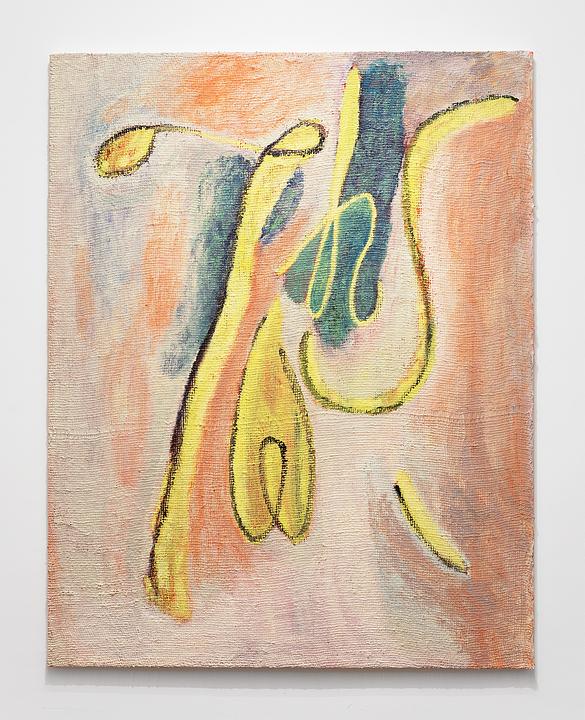

Rebecca Watson Horn

Untitled, 2022

Oil on burlap

51 x 39 in (129.5 x 99.1 cm)

Rebecca Watson Horn

Untitled, 2022

Oil on burlap

52 x 41 in (132.1 x 104.1 cm)

Ann Zhao

See chart, 2021

Oil on canvas

9 x 12 in (22.9 x 30.5 cm)

Maggie Lee

60s Cookbook, 2021

Decorative film, carpenter nails, cutouts on canvas

8 x 10 in (20.3 x 25.4 cm)

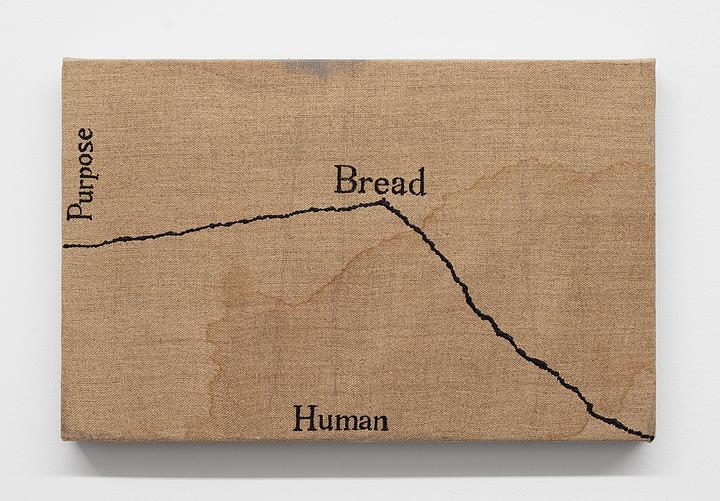

Ann Zhao

Immaterial, 2022

Acrylic on linen

9 x 14 in (22.9 x 35.6 cm)

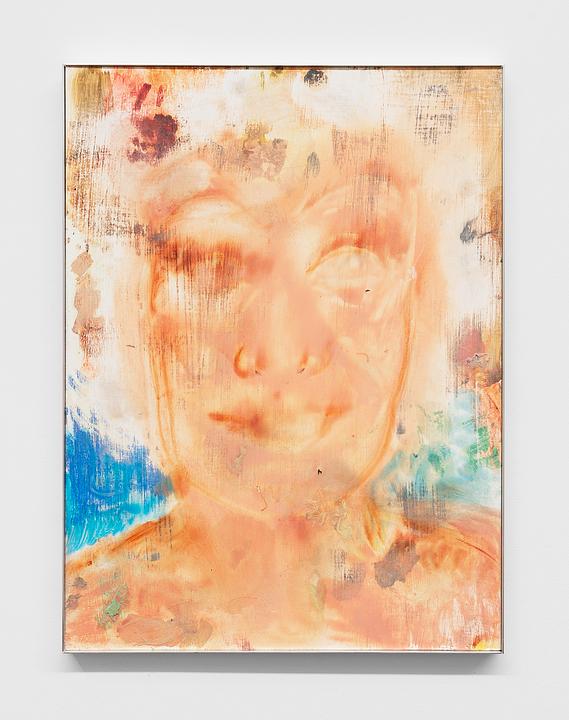

Stanislava Kovalcikova

Bromley Contingent, 2020

Oil and encaustic on panel

19.5 x 14.625 in (49.5 x 37.1 cm)

Derosia is pleased to announce The Practice of Everyday Life, a group exhibition of artists who examine ruptures and interstices in the systems that structure ordinary experience. This exhibition is titled loosely after Michel de Certeau’s text, which posits means of individual autonomy over the embedded frameworks that dictate daily behaviors en masse, proposing that language, urban design, even philosophy undermine the individual by guiding her into circumscribed and preordained behaviors and beliefs. The artists in this exhibition suspend, disregard, reconstruct, and resist these daily rhythms and patterns, excavating language, time, geometry, and more.

Richard Hawkins’ practice frequently reads as both vividly personal and promiscuously referential, with several of his series resulting from a process of studying, internalizing, and regenerating the ideas of historical artists and thinkers, the results always inflected by his own visual lexicon and biography. His works based on the drawings of Antonin Artaud catalog the playwright’s carnal iconography, while expanding on its meaning through a study of its origins. In 1936, Artaud set out on horseback in search of people “uncontaminated” by European modernism, and came upon the indigenous community of the Tarahumara in the village of Norogachi. The trip initiated a series of drawings, completed during Artaud’s stay in the Rodez Asylum (1945–1946). Sneezing suns with scrotal faces; bodies deconstructed and rebuilt from only bones, genitalia, and breasts; fanged traps; and clock faces signifying solar deities are among the drawn inventions that Hawkins integrates into his ceramic reliefs, while styling his own castrated divinities and hermaphroditic gods.

Rebecca Watson Horn paints letters untethered to vocabulary or speech, distilling them to their formal properties. The resistance to articulation in Horn’s paintings becomes analogous to painting itself—the clarity and visual immediacy, for instance, that befalls objects when observed but not named. In the works on view at Derosia, letters nestle within one another, a U cradles an S, an L spoons another S, letters are more attuned to their formal rhyming than verbal order and undermining the orientation of writing. Residing in a suspension of language and naming, Horn’s paintings invite rejuvenated visual and verbal apprehension.

Brook Hsu’s A Wanderer Plays on Muted Strings (2022) takes its title from the second book in Knut Hamsun’s Wanderer Trilogy, in which the protagonist Knut Pedersen (named after the author) leaves the city in search of peace in the countryside. Much of Hsu’s work recovers pagan characters, most notably Pan, the ancient Greek god of the wild—the basis for Knut Hamsun’s eponymous 1894 book, and the namesake of Green Panic, a vivid chlorophyllic genus primarily growing in Africa and a reference to Hsu’s frequent palette. Hsu uses green shellac ink, which deepens with each layer, so that her drawn images subtly emerge from a monochromatic field. Hsu’s image in Wanderer is based on a found image of Krishna playing the flute beneath a tree, and refers to a metaphor the artist once heard between of the flute for the heart—the instrument’s holes signify each pain the heart has endured, keeping it continually hollow for the god of love to play.

Hanna Hur’s Quad vi is titled after Samuel Beckett’s Quadrat 1+2, a made for television play featuring four cloaked figures filmed aerially. The four are choreographed to circumambulate the stage, nearly collide in its center, and neatly disperse to the four corners again-–repeatedly, frenetically, and to the beat of an anxious percussion. In act II, this routine is silenced and slowed. Similarly, in Hur’s painting, a rigorous gridded framework belies a register of materiality, labor, and time—the latter causing soft, optical vibrations on a closer read of the surface. For Hur, the lattice and the repetition it entails is a vessel to both drive and capture deep labor, obsessive focus, and a near meditative state.

Stanislava Kovalcikova’s paintings are often patinated and layered, the effect of allowing her images to materialize over time through incident and materiality. Rather than setting out to create a specific image, Kovalcikova’s durational painting practice is a process of openness and receiving. Painting female faces slightly obscured, Kovalcikova restores mystery to femininity amongst the proliferation of images of women online.

Maggie Lee’s 60s cookbook breaks down a found recipe into whimsical, sugary fragments—“sprinkle,” “powdered” “as for jelly roll,” “tart jelly sprinkle top,” “cake”—tumbling across a ground of hot pink lenticular film, studded at its edges with carpenter nails. Lee combines potent nostalgia with teen DIY aesthetics, superimposing the unabashed decadence and weirdness of 60s desserts onto materials from Y2K pop punk, her illusory surface seeming to signify the generational gap.

Naoki Sutter Shudo’s sculpture carefully applies order to nature: in Grove (2021), a considered landscape of polished sticks and tiny flowers are installed and adhered in an exacting pattern onto a painted, enameled geometric platform. Installed for a slightly aerial viewing, Grove suggests a birds eye view of nature, subject to an unusual degree of organization. The care present in Sutter Shudo’s sculpture brushes up against the broader and more pressing and sinister implications of human impact on the earth.

Kern Samuel’s work integrates materials, techniques, and forms from the everyday. A good rain is coming (2022) evolves from the artist’s earlier tondos: the work is a deconstruction of an earlier round painting which mapped a network of interior circles using sewing and color. Samuel deconstructed the circular composition using a found raisin box tab as a template, rendering the composition both undulating and interlocking. The resulting flurry of patterns and oscillations of color earn the painting its title. Old tin roof (2022) cuts the same raisin box form into strips of herringbone linen, overlaid like roof shingles and pigmented with rust—titled for the rooftops in Trinidad where his grandmother would dry cashews on hot days.

Tabboo!’s The Clock (2018) centers a radial burst of fecundity and exuberance—from an amorphous green center spring florals, greenery, monarch butterflies, glitter, punctuated by each hour of the day in the artist’s calligraphic hand. The concentric organization and radial symmetry of the painting recalls mandala painting, the meditative practice into which time is sunken, then erased. In The Clock’s form and its suggested content, time counted appears secondary to life lived.

Isadora Vogt deconstructs fairy tales found in childrens’ books from the 1950s and 1960s, supplanting the sweet and holistic and painting them into sinister settings. In Schweine (2021), Vogt’s raw brushwork obfuscates ambiguous threats beyond the central, dancing pig: a pair of eyes seem to lurk in the upper left hand corner, as do a set of claws; a thick forest awaits the pig in the upper right; and various creatures are barely articulated along the bottom periphery of the canvas, their intentions even less clear. The central character is lifted from The Three Little Pigs, the fable in which one of three pigs builds a house sturdy enough to withstand the wolf—adding to the uncertainty of Vogt’s pig’s fate.

Ann Zhao’s paintings reflect on the human body as a site for healing, prioritizing its unspoken signals above conscious and societal directives. See Chart (2021) shows the body mediated through technology: softly articulated bones as though seen through an X-ray. With her infographic title, she underscores a relationship between the body and the scientific, questioning their reconciliation. Similarly, Immaterial (2022) graphs “Bread” along the axes of “Purpose” and “Human” on raw linen. The painting initially suggests a reading of human beings as “purpose-bred,” or living solely to fulfill their vocations, yet the homonym “bread” and opaque circularity of the chart renders the concept nonsensical, again suggesting incompatibility between humanity and order.