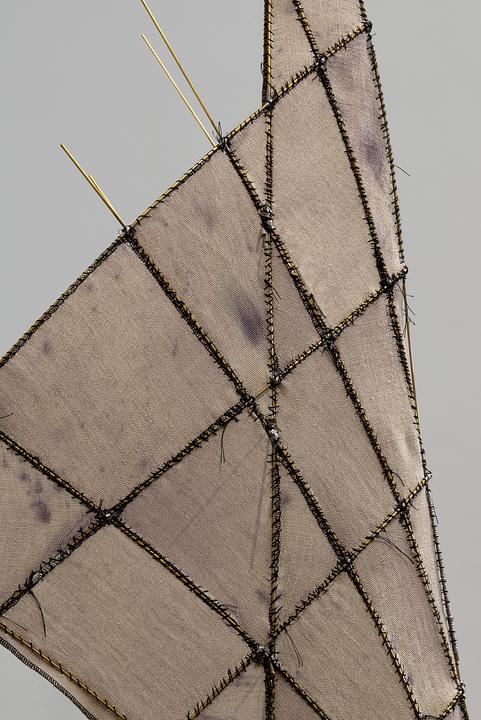

W253, 2023

Brass, copper, dyed linen

73.5 x 11.5 x 26 in (186.7 x 29.2 x 66 cm)

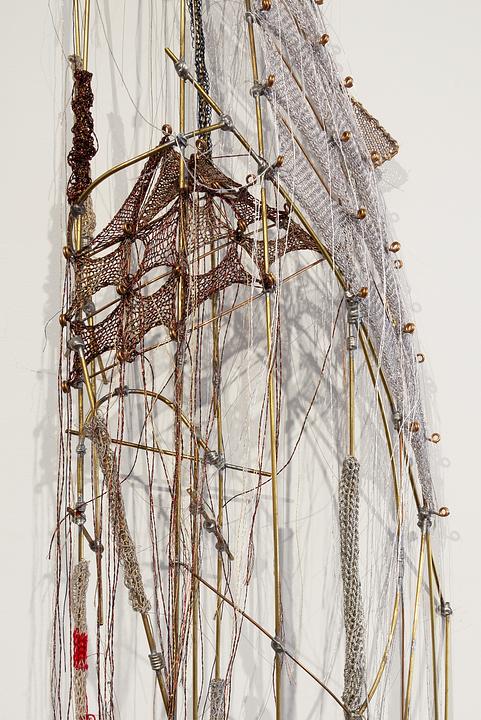

NW298, 2023

Brass, tin, copper, assorted fibers

76 x 11 x 6.5 in (193 x 27.9 x 16.5 cm)

N346, 2023

Brass, tin, copper, feather, assorted fibers

73.5 x 42 x 32 in (186.7 x 106.7 x 81.3 cm)

SE125, 2023

Brass, tin, copper, assorted fibers

88 x 5.5 x 6 in (223.5 x 14 x 15.2 cm)

Journey, 2021-2023

Graphite on paper in brass frame

17.5 x 23.5 in (44.5 x 59.7 cm)

Portrait of a Lady, 2023

Bronze

7 x 5 x 1.25 in (17.8 x 12.7 x 3.2 cm)

Portrait of a Lady, 2020

Bronze

8 x 4 x 1.25 in (20.3 x 10.2 x 3.2 cm)

Portrait of a Lady, 2023

Bronze

9 x 5.5 x 2 in (22.9 x 14 x 5.1 cm)

Portrait of a Lady, 2020

Bronze

7.5 x 5 x 2 in (19.1 x 12.7 x 5.1 cm)

Portrait of a Lady, 2023

Bronze

9 x 5 x 1.5 in (22.9 x 12.7 x 3.8 cm)

What does it mean for a garment to become its own device, outside the body?

Garment as a synthetic extension expands the presence of a body, anchoring it like an architectural structure. A garment evokes the body of a person and the fleshiness of a landscape. The conception of a body is entangled with the objects that frame it.

He paused for a moment to glance back towards the heights above; whereupon, the numerous cascades of the precipitous garden of the villa, framed in the doorway of the hall, fell into a harmless picture, in its place among the pictures within, and scarcely more real than they—a landscape-piece, in which the power of water (plunging into what unseen depths!) done to the life, was pleasant, and without its natural terrors.

(Walter Pater, Marius the Epicurean: his sensations and ideas, 1885)

If it is possible for architecture to domesticate the psychological effect of untamed nature, a garment, much like architecture, can frame the body and conjure an image of a landscape. A mandarin collar’s silhouette frames the face with an artificial border that points to an ethnic origin. The contouring lines of the collar, activated by the body, becomes code for an Oriental landscape, as echoed in its name.

Garments have converged as a form of aesthetic language, accumulated through the expressions of decorative and ornamental embellishments. They embody identities, cultural symbols, meanings, and at last, they possess souls of their own. To dress is to outwardly declare an intention.

Garments are shells of the divas inside, they are devices that drive the inner self to the surface.

It’s accurate to call garments devices due to their ability to transfigure the perception of the body and to facilitate the body in various social spaces. The invention and development of these devices have recalibrated an experience of embodiment as an aggregation of objectness. These sculptures were treated as sartorial subjects, a shell, an architecture, deconstructed and reassembled—manipulations that recall images of dismantled machines, houses, and dismembered bodies, suggesting the disruption that happens before a reform. These devices shuttle between ghostly spirit and corporeal presence, quilting landscapes and mapping the continents through their aesthetic skins.

—Covey Gong, 2023

Covey Gong (b. 1994, Hunan, China) lives and works in New York. Recent solo and two person exhibitions include Lubov, New York (2022, with Eli Ping); And Now, Dallas (2019); Bodega (Derosia), New York (2019); and Salt Projects, Beijing (2016). Recent group exhibitions include Laurel Gitlen, New York (2023); Lomex, New York (2022); Baader Meinhof, Omaha (2022); Bodega (Derosia), New York (2021, 2020, 2019); Unclebrother, Hancock, New York (2021); 50 Taaffe Place, Brooklyn (2019); Museum Gallery, New York (2018); and Mother Culture, Los Angeles (2018). His work has been reviewed in The New York Times.