Organized with GEMS

Holly Village II

Chino Amobi, Matthew Barney, Mathew Cerletty, Whitney Claflin, Shuriya Davis, Nancy Dwyer, Witt Fetter, Sylvie Fleury, Andrea Fourchy, Karen Kilimnik, Charles Long & Stereolab, Michel Majerus, Andy Meerow, Sarah Morris, Sturtevant, Christopher Williams

November 8–December 16, 2023

Organized with GEMS

Organized with GEMS

Michel Majerus

Ohne Titel, 1999-2000

Mixed media

4 pieces at 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 in (60 x 60 cm) each

Shuriya Davis

Love? (2), 2022

Oil and acrylic on canvas

24 x 24 in (61 x 61 cm)

Shuriya Davis

Out of the Way of My Release, 2022

Oil and acrylic on canvas

16 x 16 in (40.6 x 40.6 cm)

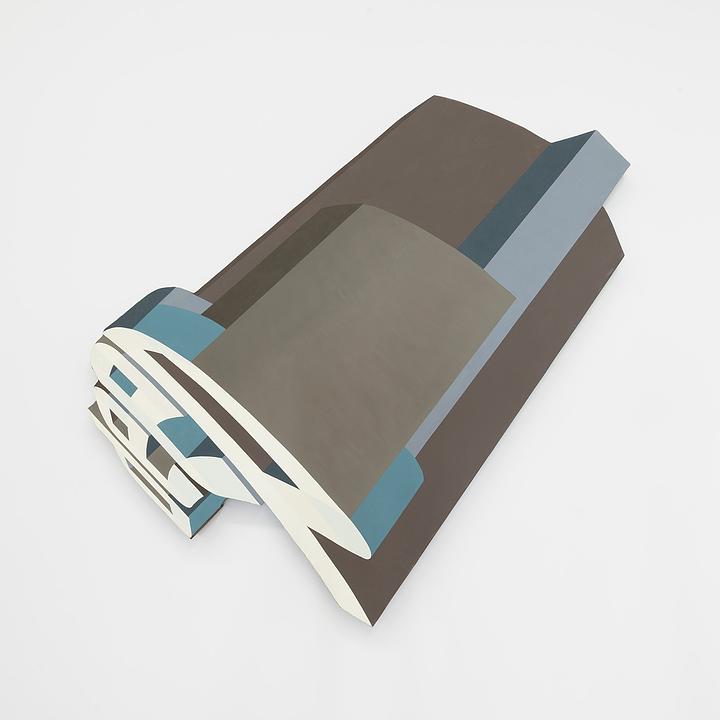

Nancy Dwyer

Deep II, 2005–2006

Acrylic on wood

49 x 72 x 2 in (124.5 x 182.9 x 5.1 cm)

Nancy Dwyer

Deep III, 2006

Acrylic on wood

48.5 x 50 x 2 in (123.2 x 127 x 5.1 cm)

Karen Kilimnik

Tabitha, 1995

Oil on canvas

20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Whitney Claflin

Smylonylon, 2023

Oil on canvas

26 x 28 in (66 x 71.1 cm)

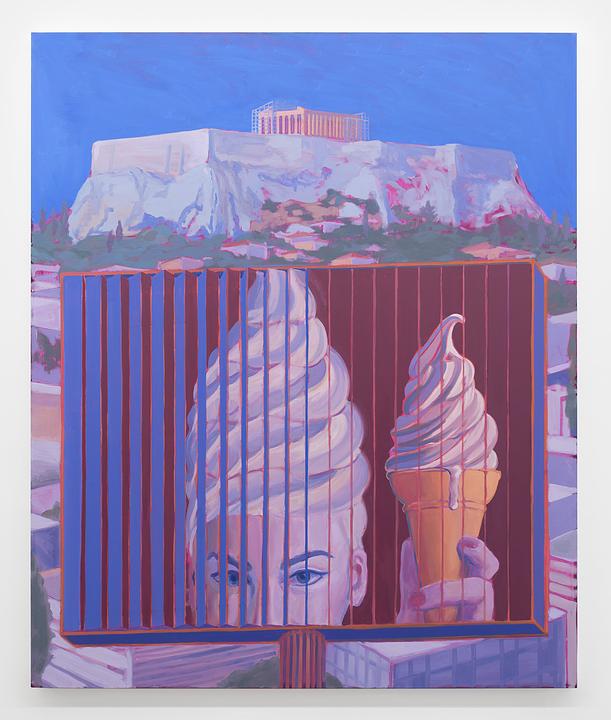

Witt Fetter

Periaktos (The Curse of Salmacis), 2023

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 in (182.9 x 152.4 cm)

Matthew Barney

CREMASTER 3: Pentastar, 2002

Edition 5 of 6 + 1 AP

C-print in acrylic frame

41.625 x 33.5 in (105.7 x 85.1 cm)

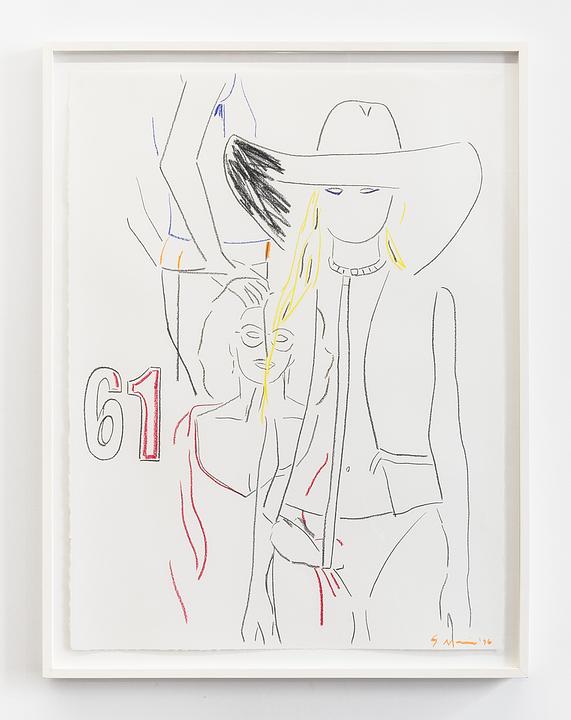

Sarah Morris

Cowgirl, 61 (Sophia), 1996

Soft pastel on paper

30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

Charles Long & Stereolab

Buloop, Buloop, 1995

Edition of 3

Rubber, sound equipment, watercooler

48 x 15 x 14 in (121.9 x 38.1 x 35.6 cm)

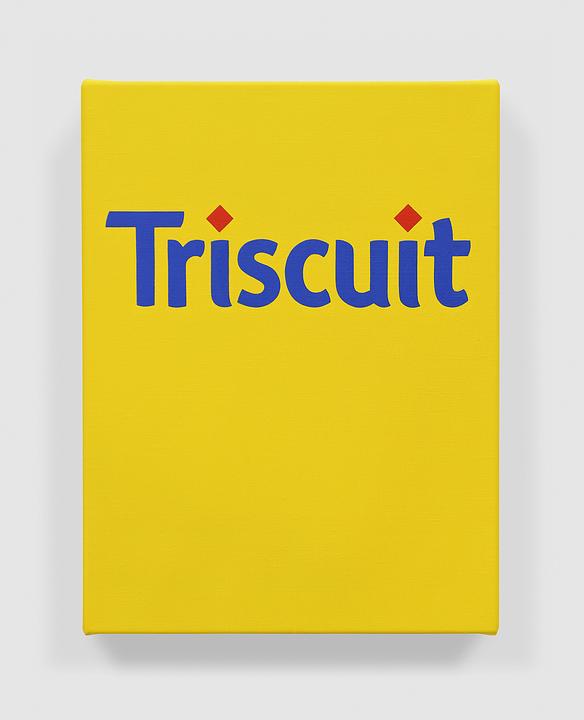

Mathew Cerletty

Triscuit, 2023

Oil on canvas

10.75 x 8 in (27.3 x 20.3 cm)

Sturtevant

Ça va Aller, 1998

Video, sound

Running time: 00:22:39

Matthew Barney

RADIAL DRILL: OTTOgate, 1991

Edition 3 of 10

Gelatin silver print in prosthetic plastic frame

15.5 x 11.5 in (39.4 x 29.2 cm)

Chino Amobi

EROICA VII, 2023

Oil on canvas

50 x 50 x 1.5 in (127 x 127 x 3.8 cm)

Andrea Fourchy

Harvest Moon 1, 2023

Oil, mylar, and mixed media collage on linen

31 x 45 in (78.7 x 114.3 cm)

Sylvie Fleury

Walking on Carl Andre, 1997

Video, sound

Running time: 00:40:05

Andrea Fourchy

Harvest Moon 2, 2023

Oil, mylar, and mixed media collage on linen

32 x 45 in (81.3 x 114.3 cm)

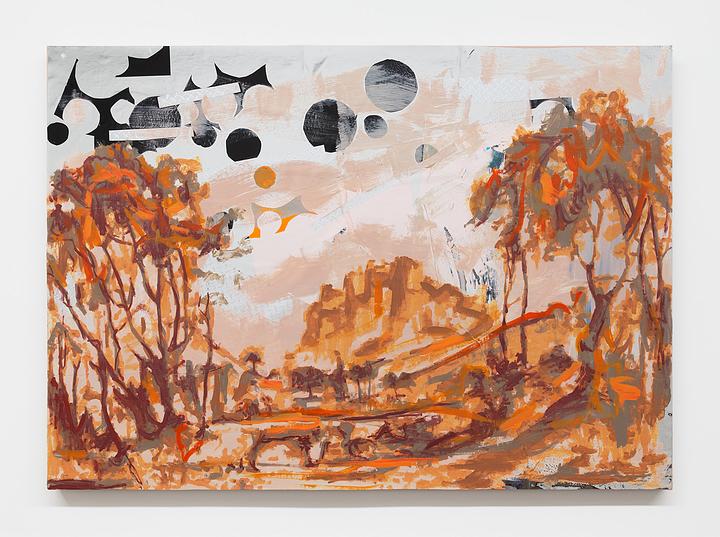

Andy Meerow

Blank, 2023

Oil and acrylic on canvas

48 x 72 in (121.9 x 182.9 cm)

Christopher Williams

Supplement, 2003

Video, sound

Running time: 05:22:00

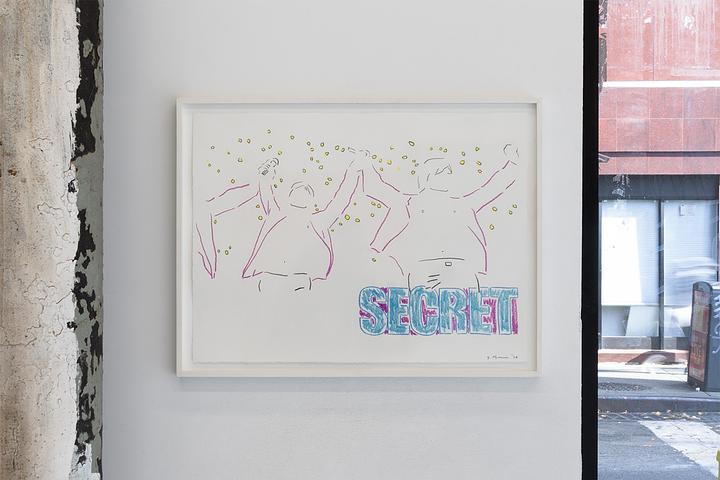

Sarah Morris

Secret, 1996

Color pencil on vellum

22 x 30 in (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

Mathew Cerletty

Nike, 2021

Oil on canvas

11 x 11 in (27.9 x 27.9 cm)

Chino Amobi

iPhone X20 Flashes Lead the Way to the Underground Shanghai Club, 2023

Oil on canvas

43 x 24 in (109.2 x 61 cm)

“you want to receive the new millennium,

for your life to be the open space that

can host the coming decades”

—@avocado_ibuprofen meme, October 25, 2023

The day after I started thinking about how to frame this show, the artist Jaakko Pallasvuo posted one of his sui generis meme carousels, one slide from which announced:

“soon it will be the year 2000.”

This exhibition vibes on the bygone phenomenon of Y2K, marked as it was by a curious fear that chaos would reign supreme after the stroke of a final decade’s midnight. Between partying like it’s 1999 to clowning like 9/11 wasn’t bound to happen, I remember that we wanted to feel like there had been a vibe shift decades before very online bozos tore each others’ feathers out over ownership of such idiocy, or, I should say, idioms. Though many of the seventeen artists included here feature text in their visual languages, none are addled by naive concerns about originality but rather grab words, forms, logos, gestures, and flair from commercial vocabularies, art history, and the free shelves or dustbins of memory.

Dying young in 2002, Michel Majerus’s legacy continues to haunt, with this show no exception. Whitney Claflin, on the other hand, is just in Germany for a while. She was the source of inspiration for the first version of “Holly Village” as staged at Derosia’s former space back in 2019, and her work is the throughline into this one, as represented by a drippy, hippy-dippy spread of disempowered flowers that don’t give a rat’s ass about forming a proper repeat. Titled in stoner-brilliance style as Smylonylon, it sets the tone for this intergenerational party where the street-styled make accommodations for an ornery, silent set of smokers whose distant smiles you just can’t trust. Karen Kilimnik’s Tabitha, for one, is from 1995, and this girl does appear too young, but isn’t that what makes her being on offer so much more alluring? What’s wrong? Don’t you see images like hers all the time? Being available to be looked at is kind of the whole point of her existence—frankly, it’s bad manners not to want her. Just ignore her dead rabbit—everything is going to be ok—would you like a Triscuit? How about Mathew Cerletty’s Triscuit? It’s done in oil—who could say no? There’s no reason!

In the barest of seams between advertising lingo and the so-called personal expression, these artists zoom in on the production of their own experiences and then enlarge details beyond recognition or use. Nancy Dwyer’s works are as if some teacher once gave her a vague prompt to be more “dynamic” in her visuals and instead of striving for an “A” she decided to burn the school down and carve a “for sale” sign out of the wreckage. Shuriya Davis’s abstract canvases recuse themselves from representation and any false pride attached to performing an identity. On the other hand, Andy Meerow’s work trumpet blasts that he’s optimizing for work, fitness, and perhaps even leisure—his painting Blank says “blink” right-side up, and “Tuesday Morning” sideways because the difference doesn’t matter when every day is branded, written out, and used up like the last of the gym towels no one has especially ever enjoyed.

Blink, and now it’s Wednesday in the year 2000; blink and it’s Thursday in 2023 and we’re still wrestling with the long tail of Matthew Barney’s morass of rituals styled to runway perfection; the silver gelatin and prosthetic plastic is a combo meal of signifiers and it might be best to feast on that by the water cooler with the work buddies—even better if it could be Charles Long and Stereolab’s improvised canteen. “Pop Quiz” from 1995 is the song it plays, and one answer could be another from the ’90s, like Sarah Morris’s pair of contour drawings.

It was in the past couple of decades that brands took on a kind of sentience, and it became a matter of course that the individual self was a “personal brand.” Sturtevant and Christopher Williams presciently worked and work exclusively within such parameters—they don’t have a bridge to sell you, but they are the bridges that other artists drive back and forth on while trying to understand this terrain of Now. At the intersection of cool customer and hustling salesman is Sylvie Fleury’s femme-centric 1997 video Walking on Carl Andre where two women in stilettos tread upon him. A deadpan fealty to delivering what’s proposed to be on offer is what sets these artists apart from the salaried workers in marketing. While a consumer good makes promises as a markup on disappointment, artworks explicitly propose and deliver the letdown, leaving a nice vacuum in the wake where we can actually think, for once, about what we really want. What do we fantasize about at this point? Chino Amobi seems to delicately mock the high finish of futurist visions from the past à la Blade Runner (or is it Blade Runner 2049 [2017]?) with his starkly detailed oils rendered in the colors of a red-light district with amped-up titles. When will my iPhone lead me to the underground Shanghai club? Who do I need to talk to at Apple to achieve my own personal singularity? Or, barring transcendence of the Earth-ly real, how do I become at one with mid-aughts Jacqueline Humphries paintings the way Andrea Fourchy does? How do I find a life-altering dream in a billboard the way Witt Fetter did?

There’s a time lapse and these pictures register the dissonance between the projections we once had about the future and reality. It takes time to slide back, and forward—sloshy, like a dream. Or, it’s like how they said “move to New York City”; make your name, they said; but, you know, it really takes a village to become anyone at all. That’s just showbiz, baby.

—Paige K. Bradley

Special thanks to Air de Paris, Barbara Gladstone, David Zwirner, Front Desk Apparatus, Karma, Karma International, Lomex, Meredith Rosen Gallery, Petzel Gallery, Colton Saunders and Galerie Timonier, Stars, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Theta, and von ammon co.