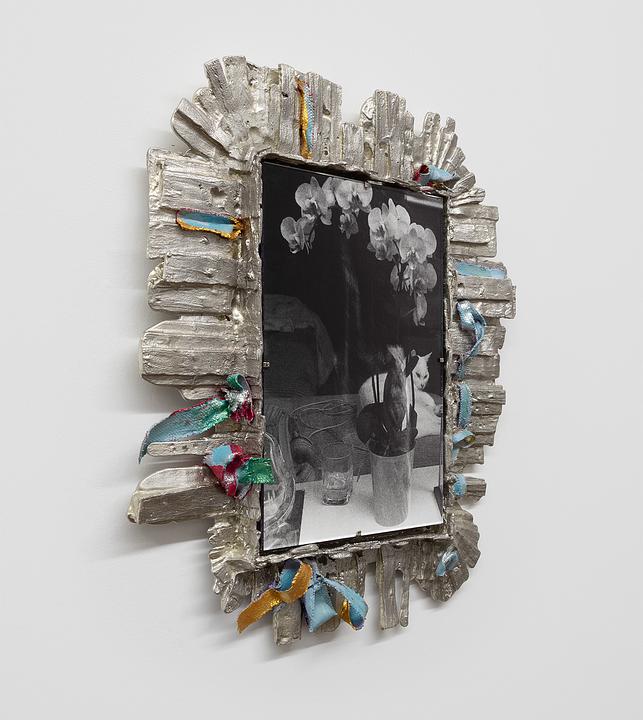

Calamity, 2024

Silver gelatin print in pewter and painted linen frame

17.5 x 15 x 1.5 in (44.5 x 38.1 x 3.8 cm)

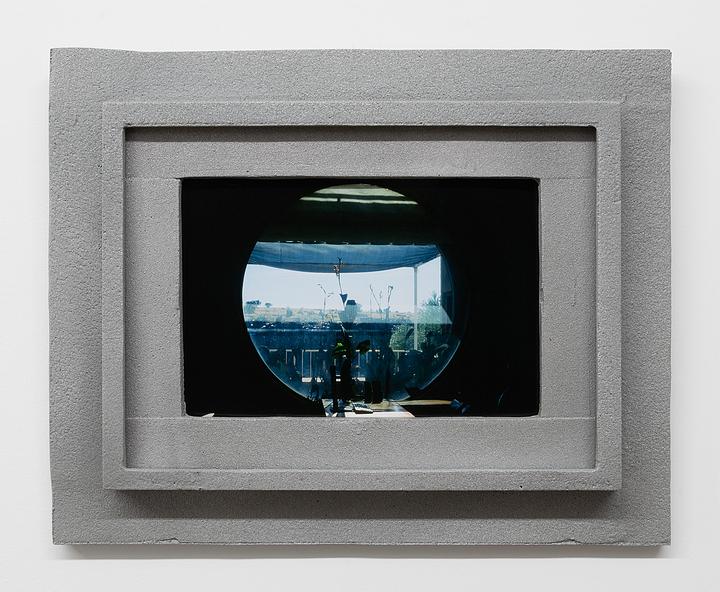

Neither Flowers Nor Doors, 2024

Digital C-print in aluminum frame

12 x 14.75 x 1.5 in (30.5 x 37.5 x 3.8 cm)

Earthen & CA, Cannon County, TN, 2024

Digital C-print in aluminum frame

12 x 14.75 x 1.5 in (30.5 x 37.5 x 3.8 cm)

Chris, Helen and Mac, 2024

Digital C-print in aluminum frame

12 x 14.75 x 1.5 in (30.5 x 37.5 x 3.8 cm)

Lavender Pit, 2024

Silver gelatin print in pewter and painted linen frame

15.5 x 13 x 1.5 in (39.4 x 33 x 3.8 cm)

Oddly Enough 1/1/2023, 2024

Digital C-print in aluminum frame

12 x 14.75 x 1.5 in (30.5 x 37.5 x 3.8 cm)

Imagined Beauty Begins Now, 2024

Digital C-print in aluminum frame

12 x 14.75 x 1.5 in (30.5 x 37.5 x 3.8 cm)

Animals for Pleasure, 2024

Silver gelatin print in pewter and painted linen frame

15.5 x 13 x 1.5 in (39.4 x 33 x 3.8 cm)

This exhibition of new photographic work features eight images in handmade artist frames. Five color photographs are set in cast aluminum frames and the three black and white photographs are set in pewter frames. Neither photo nor frame are secondary to the other. They are haptic and irregular—like petals, like piles, like sedimentary rock, like bark, like a crown, like a burst of light, exuding something molten now cooled.

Our encounter with each photograph is mediated by sparkling aluminum, pewter, paint and fabric, and this materiality meets our own: tendrils, ribbons, fingers, bows and knots intertwine. The photos are not bound by their frames as the image extends into our physical space inviting an embodied relational looking. The frames emphasize pleasure and are excessive, even awkward. They remind me of Decorator Crabs that add seafloor objects to their shells, heavy and lopsided, their precarious assemblage suggesting a secondary utility.

In Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia, Roger Caillois describes organisms’ environmental relationality in terms of personality, or “the connection between consciousness and a particular point in space.”¹ He argues, “Among distinctions, there is none more clear-cut than that between the organism and its surroundings; at least there is none in which the tangible experience of separation is more immediate.” As these decorators scuttle the ocean floor accumulating shells and rocks, they become indistinct from their surroundings. In doing so, they extend the watery conduit around the body through which they perceive. Caillois describes the crabs' condition of being, as “legendary psychasthenia, a disturbance between personality and space.”

Rooney’s works posit that the interlinked qualities of pleasure and utility are in tandem, inextricable and ever-present. In her essay, Fingereyeyes: Impressions of Cup Corals, Eva Hayward offers a queer reading of sensuous meaning-making through an experience she had with the titular marine invertebrates.² While assisting researchers studying the metabolic rates and reproductive strategies in coral communities, she experienced what she calls fingereyeys, which holds an idea of interspecies sensing and apprehension through permeable and indistinct boundaries. Hayward recalls Gaston Bachelard's metaphor for water as imagination made material.³ The qualities of water exist everywhere and have the capacity to compel us to see through it, beyond our own image. For Bachelard and Hayward, water allows us to see the world seeing itself, revealing and reflecting.

In each of Rooney’s works a simple and photographic redoubling occurs. The photographer looks through the viewfinder to a second barrier—a gate, window, fence, or flash creates emotive and imaginary spaces beyond visual or physical accessibility. We are invited, as viewers, to imagine another’s sensorium. Rooney’s works emphasize a presentness which a fixed image would seem to defy by way of its having-been-ness. Here, imagined beauty also reaches forward, toward the what-could-be. We are endlessly searching for connections, many of which are already here with us— enchanting, looping, physical, messy, and insistent.

—Earthen Clay

_______________________________

¹ Roger Caillois and John Shepley, Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia. (October, Vol. 31, 1984), 17–32, https://doi.org/10.2307/778354.

² Eva Hayward, Fingeryeyes: Impressions of Cup Corals. (Cultural Anthropology, Issue 25), 577–599, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01070.

³ Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. (Dallas: Pegasus Foundation, 1983), Edith R. Farrell, trans.