Curated by James Michael Cardoso-Shaeffer

Holly Village

Lutz Bacher, Trisha Baga, Whitney Claflin, Rochelle Feinstein, Jake Levy, Greg Parma Smith, Josef Strau, Trevor Yeung

September 13–October 20, 2019

Curated by James Michael Cardoso-Shaeffer

Curated by James Michael Cardoso-Shaeffer

Greg Parma Smith

Oriental White Ibis with Aura, 2017

Oil and jewels on canvas

48 x 48 x 1.5 in (121.9 x 121.9 x 3.8 cm)

Trisha Baga

Lesbo Island Echo, 2019

Glazed ceramic, Amazon Echo Dot, The Metropolitan Opera 2019–2020 season calendar

11 x 13 x 12 in (27.9 x 33 x 30.5 cm)

Jake Levy

Costume for Nurse One, 2019

Linen and corduroy

59 x 41 in (149.9 x 104.1 cm)

Jake Levy

Costume for Nurse Three, 2019

Cotton

60 x 37 in (152.4 x 94 cm)

Trevor Yeung

Night Mushroom Colon (Six), 2018

Night lamps, various plug adaptors

5.9 x 5.9 x 7.9 in (15 x 15 x 20 cm)

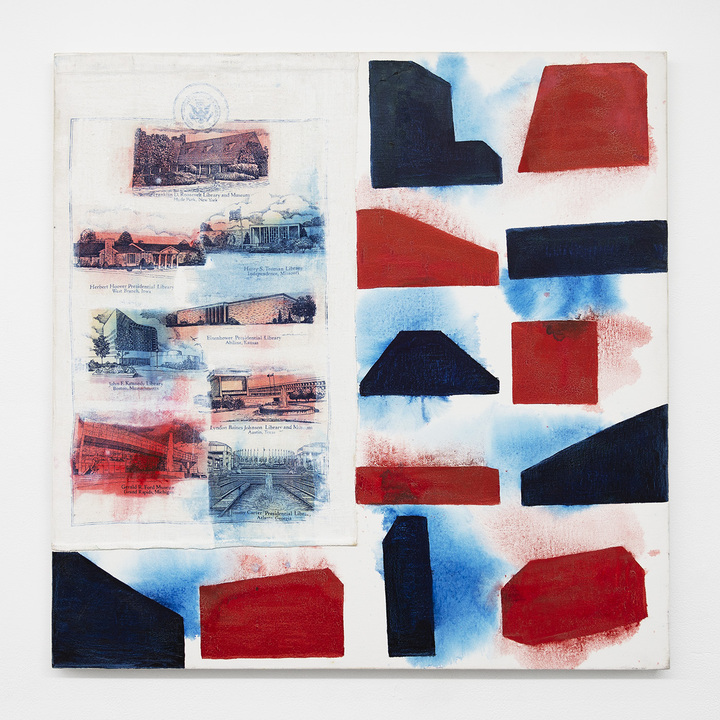

Rochelle Feinstein

Wonderful Sex (The Wonderfuls), 1992

Oil, fabric, printed dish towel on canvas

33 x 33 in (83.8 x 83.8 cm)

Lutz Bacher

Angry Bird, 2016

Printer polyester, helium balloon

43.3 x 31.5 x .4 in (110 x 80 x 1 cm)

Whitney Claflin

Fax Mish, 2019

Oil, acrylic, glitter, letterset, ballpoint pen, carbon transfer, gold foil, thread, and beads on wool suiting

20.5 x 14 in (52.1 x 35.6 cm)

Josef Strau

Betrayal Lamp, 2006

Mixed media lamp

57 x 17 x 23 in (144.8 x 43.2 x 58.4 cm)

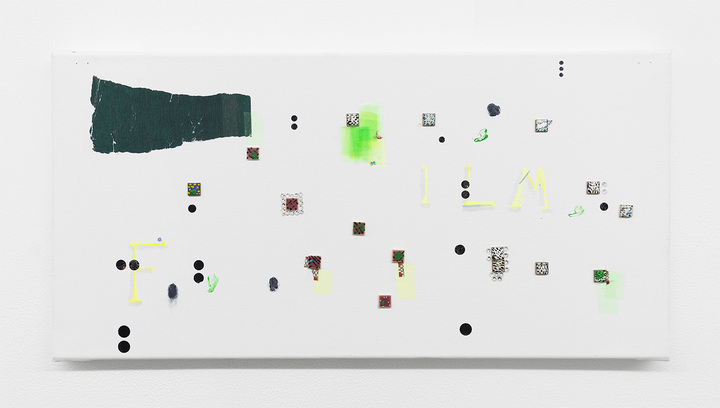

Whitney Claflin

Register, 2019

Oil, acrylic, tile, glitter, tape, nail decals, letterset, and found flyer on linen

12 x 24 in (30.5 x 61 cm)

Jake Levy

Costume for Nurse Two, 2019

Cotton

57 x 34 in (144.8 x 86.4 cm)

The idea for this exhibition came up at a sports bar in the East Village early this summer, when Eric Veit, Joel Dean, and I met to watch the NBA Finals between the Toronto Raptors and The Golden State Warriors. I’m not a follower of basketball, but I enjoy the comraderie of watching sports—this is likely a vestige of my upbringing in a family of four brothers, where I was the youngest. It was raining aggressively that night and the bar was near capacity. Among those seeking cover was a couple who caught my eye when they stood near us. They seemed especially fond of each other, as well as visibly drunk. They kept aggressively making out, despite the generally unromantic atmosphere. Personally, I couldn’t imagine a less arousing setting than this place, but I suppose it’s possible that the smell of stale beer mixed with mozzarella sticks can really stoke the flames for some people.

I wasn’t particularly engaged with the game, so I steered our own table’s conversation, naturally enough, to art. Eric brought up the work of Whitney Claflin, a painter and friend of mine. Eric indicated his admiration for her talents as a painter but also as an artist whose engagement with myriad subjects such as music and poetry are also encompassed by her practice. There are lots of points of entry into her paintings, and for myself I often think of her abstract work like a condensed JMW Turner dusk sky. Like the mad paintings Turner left unfinished shortly before his death, Whitney’s abstractions share a similar affinity for depth and layers of color. The strokes in each artist’s work compact a frenetic energy that in unison flow beautifully. Also a poet, Claflin describes her paintings with thoughtful grace. When asked, she shares a thorough account how a painting came to be—the peculiarities behind each material in a collage, precise references and motives behind particular decisions, and the personal stories which so often inform her compositions and their eventual titles. Each painting feels a bit like an iceberg, signaling great depth beneath the surface.

The basketball game playing on the multiple screens in the bar would sporadically interrupt our conversation. Toronto, who was the chosen favorite at our venue, was clearly going to lose. A few fans of Golden State in a table next to ours were emboldened by their team’s inevitable victory and began to taunt others in their proximity. The couple embracing next to us couldn’t have been bothered.

This line of discussion led us to Trisha Baga and how her way of working might rhyme with Whitney’s. What struck me as most similar between their practices, however, is how literal and descriptive Trisha’s press releases can be despite the abstract nature of her work. There’s also the matter of vibe: I’m positive writings on Whitney and Trisha’s work share many adjectives like psychedelic, abstract, idiosyncratic or even intimate. I had first seen Trisha Baga’s work at Société in Berlin in 2013. Baga’s work has always transfixed me—her installations and films have reflected for me a perfect balance between macro and micro. She confidently edits her exhibitions and never overwhelms a space. Like Whitney, Trisha would often involve personal histories into her work.

As the rain cleared up and the basketball game ended, the couple took their public affection to a different venue, and Eric invited me to continue this conversation with him and Elyse Derosia, the other half of Bodega, for a potential exhibition at their gallery. Before departing, I remember running into Quintessa Matranga and Rafael Delacruz—unwittingly this sports bar had managed to attract a gaggle of BFAs.

I’m hesitant to put forth a conceptual framework for this show, but if pressed, I would say it stems from the quandaries of communication, miscommunication, and muteness: how private exchanges can greatly affect the outcome of a practice. I kept thinking about this quote from Renata Adler’s Speedboat:

Last night at dinner, a man said that, on principle, he never answers his telephone. Somebody asked him how he reached people. “I call them,” he said. “But suppose they don’t believe in answering either?” I thought of phones ringing all over New York, no one answering. Like people bringing themselves off in every single adjoining co-op of a luxury building. Or the streets entirely cleared of traffic, except ambulances.

I set up a studio visit with Whitney for the next week to hear her thoughts on the connections between her practice and Trisha’s. It’s important to describe her studio, which also serves as her apartment. While her process contains the traditional materials of oil paint on canvas, her studio is set up is atypical. The studio, located in Greenpoint, has peculiar lighting compared to the traditional atelier. In contrast to the abusive bright lights used to mimic the coldness of a gallery’s walls, or the traditional natural light of painters’ studios, Whitney has adorned her studio with colored Christmas lights, red, green and blue lightbulbs, as well as the blinking neons emanating from a CD player on her bookshelf.

It was in this environment that I brought up the work of Trevor Yeung. Trevor, a Chinese artist based in Hong Kong, first crossed my radar with a series of sculptures of mushroom-shaped night lights plugged into each other. Trevor’s practice also considers the dichotomy of private and public, how the personal can be transformed into the communal. The artist uses these nightlights to bring to mind our own intimate spaces, however the works dually showcase isolation.

Affinities with other artists cropped up throughout Whitney and my conversation, arriving as abruptly as solar flares. Whitney brought up her former professor Rochelle Feinstein, whose diverse practice often engaged collaboratively with peers. Particularly what came up was a piece included in her retrospective at the Bronx Museum whose materials were composed of a picture and its packaging given to the artist by Rachel Harrison. This private exchange was translated by Rochelle into a public artwork, exhibiting how interpersonal exchanges inevitably influence an artist’s practice.

I left Whitney’s studio thinking of a particular series of work by the artist Josef Strau that would fall nicely within the conversation about community. Strau’s lamps, which have appeared in group and solo exhibitions in the past decade, have taken several variations, however what is constant (beyond the materials) is a conceptual relationship between objects and text. In the artists own words, the works deal specifically with “inner and exterior spirits.” These pieces seemed to summarize what was guiding this exhibition: the wedlock of a collective discourse and the objects that manifest themselves therein.

Greg Parma Smith, an artist based in Brooklyn, likewise fell into dialogue with the works I was considering for the show. Other than working collaboratively with artists for two-person exhibitions, such as a recent show with Bill Hayden at Galleria Federico Vavassori in Milan, Greg is open to how the content of his work derives from personal anecdotes. Akin to a few of the other artists I was considering, despite his contemporary influences Greg has a fairly traditional practice. Like Whitney with her abstract oil paintings or Trisha with glazed ceramic sculptures, the content of Greg’s paintings is rather conventional: still lifes of fruit, sitting nudes, and birds in flight.

It was from here that the exhibition took an important turn in its evolution. A conservative approach to curation dictates that all shows thread a specific conceptual link between every work and artist. This connection should serve as a theoretical argument for the existence of each exhibition. What was becoming increasingly clear for this show, however, was that it illustrated more of an atmosphere, a sensation, and a particular energy than a specific hypothesis. It was in its lack of direction that I found its justification.

If there was one artist who could claim ownership over this show’s reflections on opacity, I could think of no one more qualified than the enigmatic Lutz Bacher. As this show was organized in the wake of her death, it felt important to acknowledge her as a literal ghost in the room. Of all the wildly heterogenous works in her oeuvre, the ideal piece that came to mind was her ‘Angry Bird’ sculpture showcased in her exhibition ‘Open The Kimono’ at Galerie Buchholz in 2018. This piece stuck out for me within that particular show because it was the only work that had no clear partner, no other piece within the exhibition spoke directly to it. The work behaved as a red herring, taking you immediately out of that room and into the world of Lutz Bacher. The bird’s comically large eyes scowled at you from the corner, like an impatient overseer, scrutinizing your movements in the space. The angry bird is like a mascot for this exhibition.

As my ideas for the concept of the exhibition matured, I kept returning to themes of community. Hoping to take the show outside of a specific art context I wanted to engage with someone who I wouldn’t typically think of as an artist however was deeply intertwined within New York’s art world. Jake Levy, a fashion designer, flowed effortlessly into the exhibition proposal. Jake had not only participated in art adjacent fashion projects like Sofia Paris but had also styled many of my close friends, including Whitney.

Leading up to the opening, I struggled excessively over how I would justify the presence of all eight artists being in the same exhibition. Recently, a friend spoke to me about her own trials in curating an exhibition at the gallery where she worked. She mentioned she had struggled with the conceptual skeleton for her show, however in the end she felt “she just wanted these artists in the same room.” Press releases are burdensome as they force the museum, gallery, curator, artists, etc. to justify their actions, whereas this isn’t a task we usually demand from art itself. Wanting to avoid writing a vague poem for the press release, I was compelled to write how these things came to be in an earnest and direct way. Had there been a parable for this exhibition, however, I could not think of anything better than that couple intimately kissing in public at the sports bar the night I met with Eric. Like much of the art in this room or like the seemingly unnecessary details I included in this press release, these artists and myself have chosen to make something personal available to all. I wrote this press release while at my mom and dad’s home on August 15th, 2019. My mother, who has proofread all my essays since elementary school will be the first to see this draft. The next set of eyes will be Nick Irvin, and likely Jordan Barse if she has time. The last set of eyes will be yours, in the room, where all these artworks live. In the end it’s important for things to just exist for the sake of existence.

—James Michael Cardoso-Shaeffer

The title for this exhibition is a portmanteau of Hollywood and East Village and is also the title of a Whitney Claflin painting not included in this show.