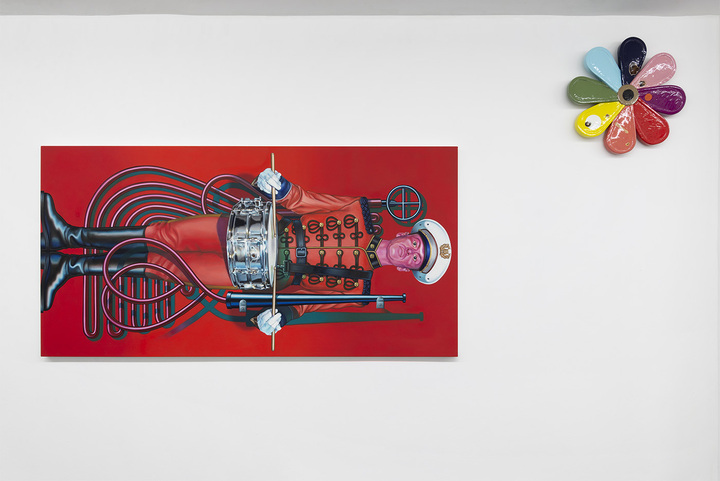

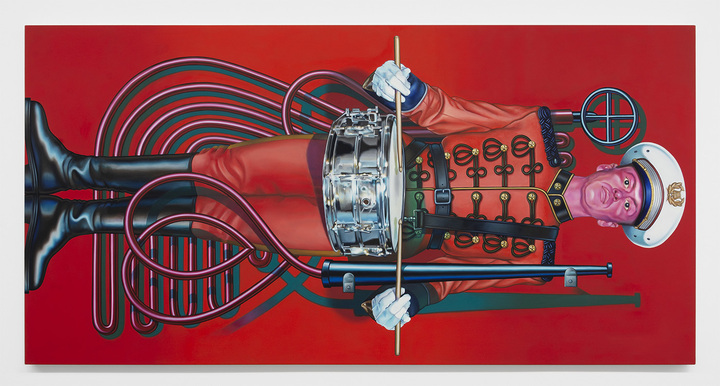

Clean Machine, 2018

Oil on canvas

36 x 72 in (91.4 x 182.9 cm)

Wind Tire tak tak tak Rainbow, 2018

Acrylic and polyurethane on basswood with driftwood and drumstick inlays

20 x 20 x 1.75 in (50.8 x 50.8 x 4.4 cm)

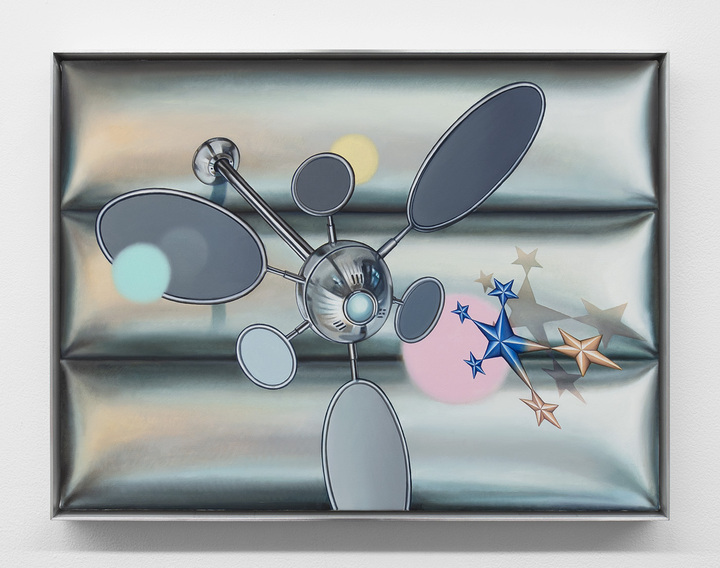

Asleep in a Fish Can, 2018

Oil on canvas, aluminum frame

15.5 x 20.5 in (39.4 x 52.1 cm)

Wind Tire Flower, 2018

Acrylic and polyurethane on basswood with driftwood and drumstick inlays

20 x 20 x 2.5 in (50.8 x 50.8 x 6.4 cm)

Founder’s Green, 2018

Oil on canvas, aluminum frame

20.5 x 15.5 in (52.1 x 39.4 cm)

Wind Tire Pink, 2018

Acrylic and polyurethane on basswood with driftwood and drumstick inlays

20 x 20 x 1.75 in (50.8 x 50.8 x 4.4 cm)

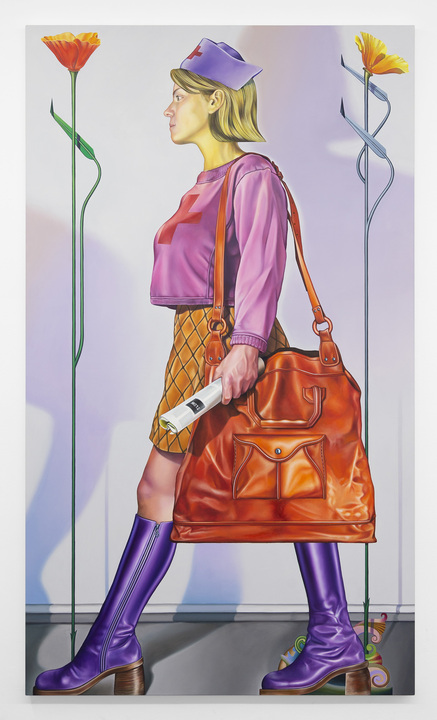

Poppies from a Tray, 2018

Oil on canvas

72 x 42 in (182.9 x 106.7 cm)

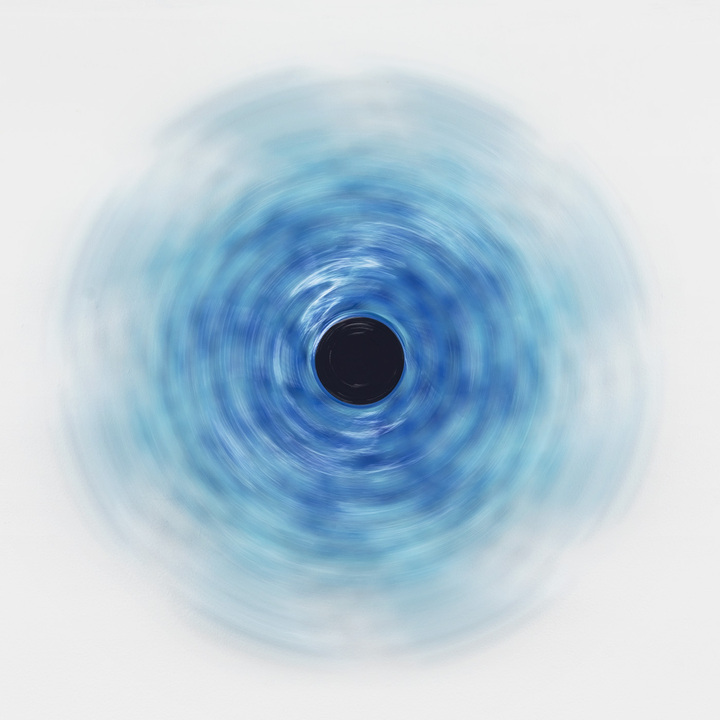

Wind Tire Blue, 2018

Acrylic and polyurethane on basswood

20 x 20 x 1.75 in (50.8 x 50.8 x 4.4 cm)

Sunbeam, 2018

Oil on canvas, aluminum frame

15.5 x 20.5 in (39.4 x 52.1 cm)

Wind Tire Cher, 2018

Acrylic and polyurethane on basswood

20 x 20 x 1.75 in (50.8 x 50.8 x 4.4 cm)

Though “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields Forever” were among the first and most pivotal songs recorded during the Sgt. Pepper sessions, they never made it to the album. The bigwigs at EMI, impatient with the length and cost of the Beatles’ psychonautical studio experiments – these two songs alone clocked 105 hours of studio time – demanded a product, and so the two became a double A-side single in advance of the album. This meant exclusion from the final LP, because by then-prevalent industry logic, customers would surely feel duped to pay for the same song twice. The songs would only find their way to a full-length with the US version of the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack, whose original UK double-EP structure was deemed too fussy for US audiences. So the tracks were added, rather clumsily and without the band’s blessings, as golden padding to round out the soundtrack to what’s otherwise considered to be the Beatles’ biggest flop. Today, fifty-one years out from their release, it surprised me to realize these iconic songs weren’t on their iconic album – but maybe that doesn’t matter, because what we love is the myth.

I didn’t grow up listening to the Beatles, yet I feel like I’ve internalized them. Like the Jesus they were “bigger than,” the wake of their influence on our parents’ generation was too broad to not get caught up in, even if only through inoculations of reference, parody, and branding. They’re the codex. Several of Orion’s new paintings sprout from the imageries of “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields” as though they’re the unconscious itself: “Poppies from a Tray” and “Clean Machine” both take their titles and motifs from the former’s lyrics, and “Founder’s Green” depicts a warped slice of the bright red Liverpool gate to which fans still make pilgrimages, thanks to the legend behind the latter, even though it’s now a facsimile.

So, while writing this text, I streamed those songs on repeat, plus Sgt. Pepper for good measure, while staring at JPEGs of these and the other paintings. Like listening to those songs now, the paintings feel like shreds of childhood half-memories made manifest, and fleshed out with so much lurid detail that it feels confrontational: seeing as a child sees, but with all the scrutiny of an adult. In one painting we have a GIRL, with all the blunt, basic trappings of femininity, and in the other a MAN, in uniform, rigid, broad-shouldered and tall. Cartoonish costumes draped over real people, one perfectly profile and the other perfectly frontal, before a flat backdrop: a Technicolor fantasy teeming with improbable detail.

Writing in 1981 on the legacy of the Beatles’ trippy years, poet Blake Morrison described “the Beatles’ psychedelic landscape [as] more Lewis Carroll than William Burroughs; all that they’d done was re-open the nursery door. ‘Marmalade skies’, ‘newspaper taxis’, ‘rocking horse people’, ‘kaleidoscope eyes’, ‘marshmallow pies’: it wasn’t a cleansing of perception but a visit to toy town.” Orion’s paintings give you toy town *with* cleansed perception. They know that the follies of Carroll carry an undercurrent of dread at least as deep as Burroughs’. As it’s happened, so did the whole legacy of the ’60’s: its utopias are now distant enough for us to remark unromantically upon their naïvetés, their fallout in the ‘70’s, how the Aquarian-Age hopes failed to halt the machines that continue to clamp down on us today, etc., etc., etc. To the dismay of their more radical contemporaries, ambivalence ultimately proved prophetic within the Beatles’ vanguardism. Their sunshine wasn’t without noir: Strawberry Field was a Gothic Revival orphanage, and Penny Lane’s nurse sells poppies to raise funds for mutilated World War I veterans. Sorrow is the tacit backdrop to Paul and John’s saccharine romps of observation. Looking at Orion’s paintings of lobsters and tomatoes, California poppies, a quilted skirt, and a fire hose, I wonder what’s behind our visions, we children of flower children, as the breeze blows the plaid pinwheels.

—Nick Irvin