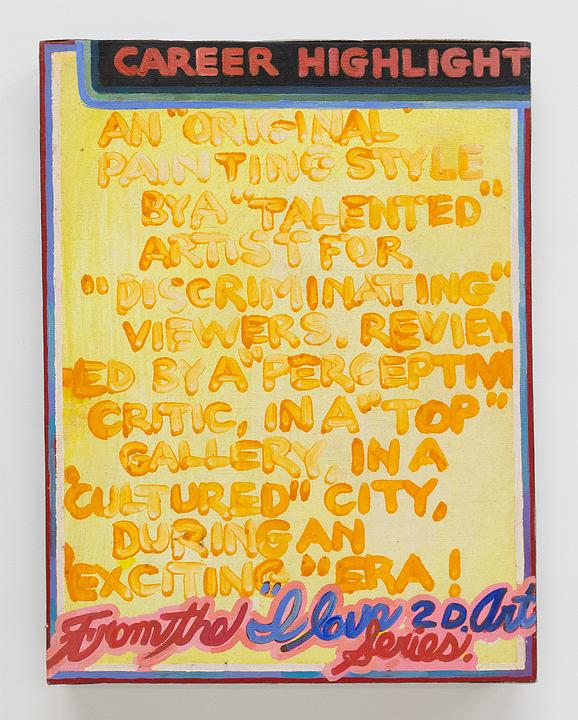

Success, 1970

Acrylic on canvas

20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

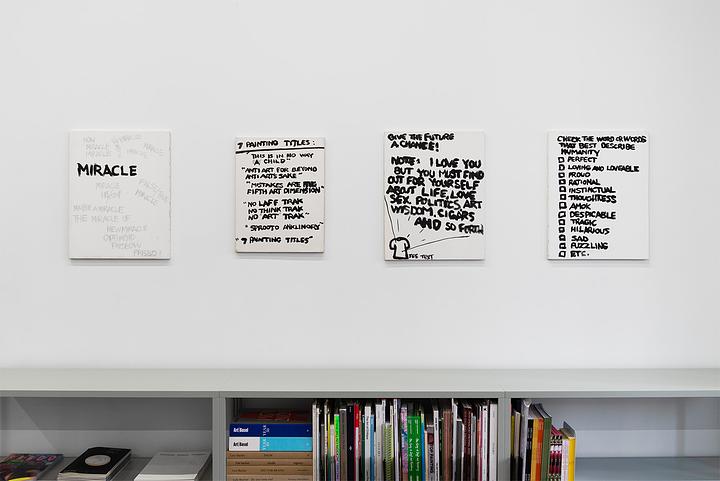

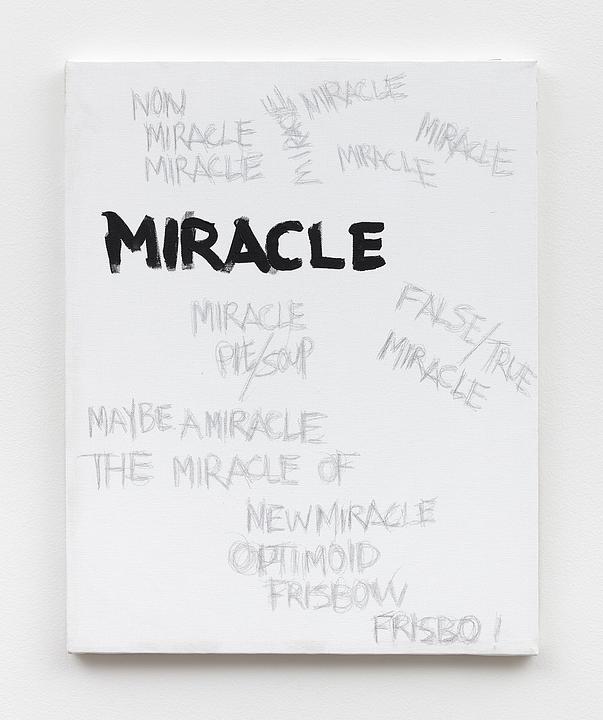

Miracle, 2010s

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

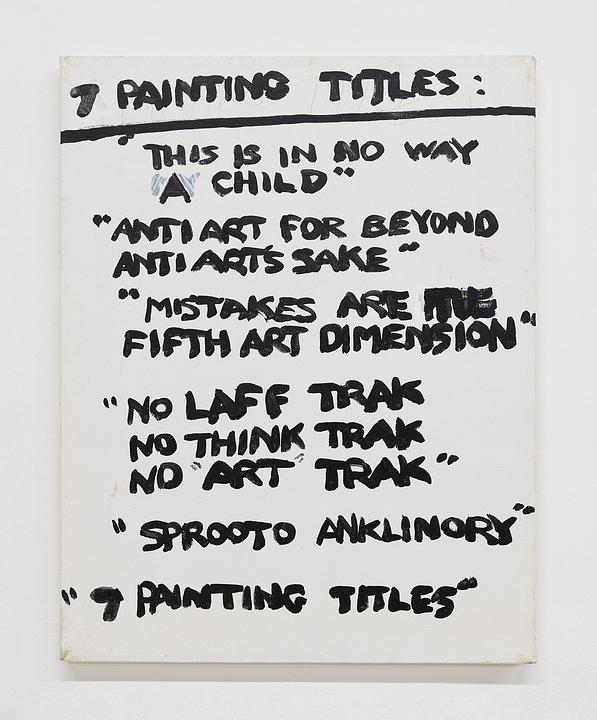

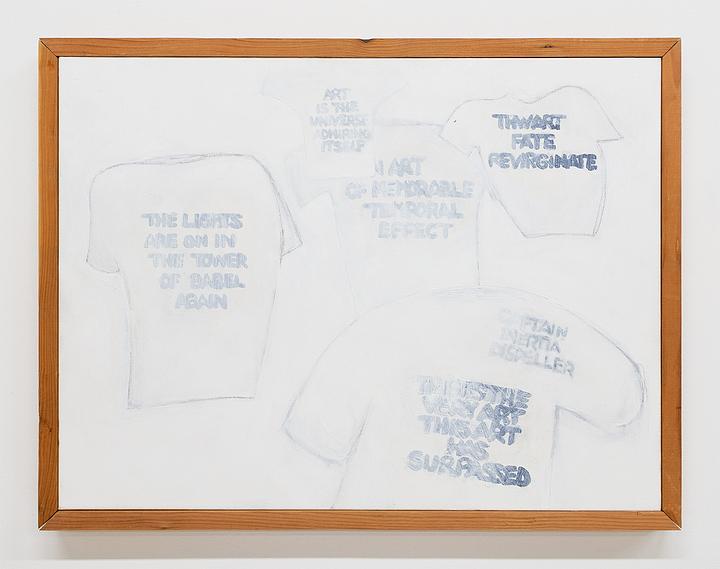

7 Painting Titles, 2000s

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 14 in (45.7 x 35.6 cm)

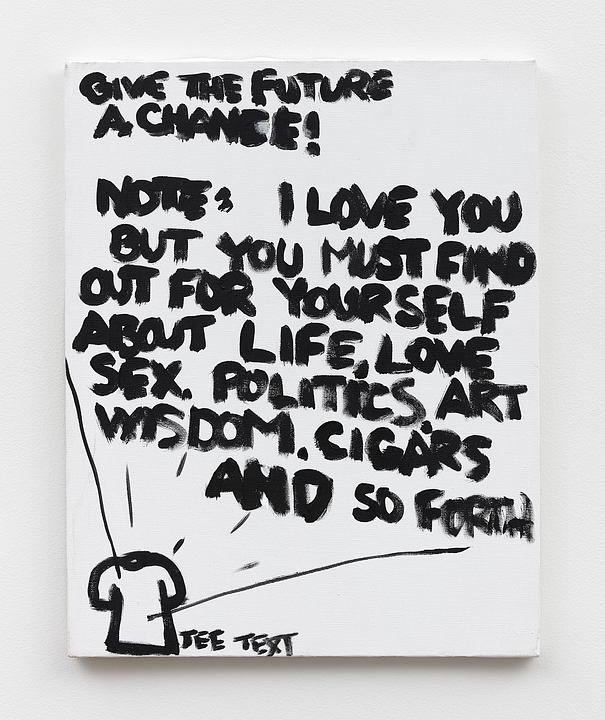

Give the Future a Chance!, 2010s

Acrylic on canvas

20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

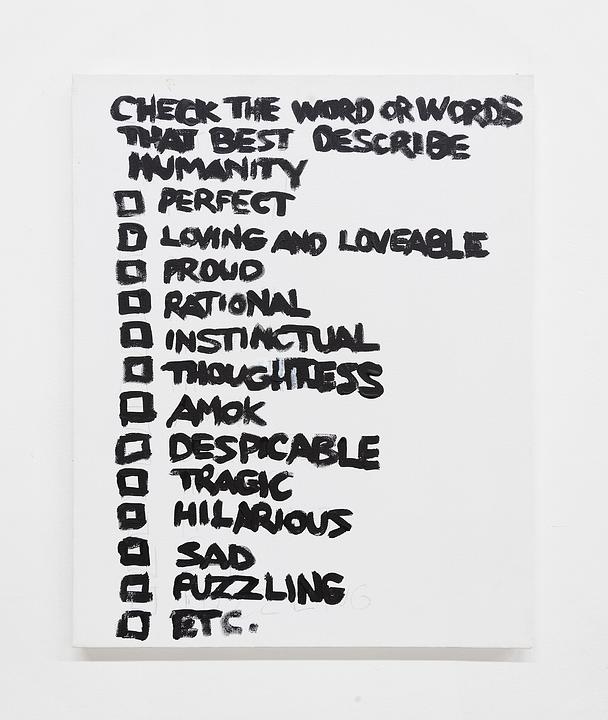

Check the Word or Words That Best Describe Humanity, 2012

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

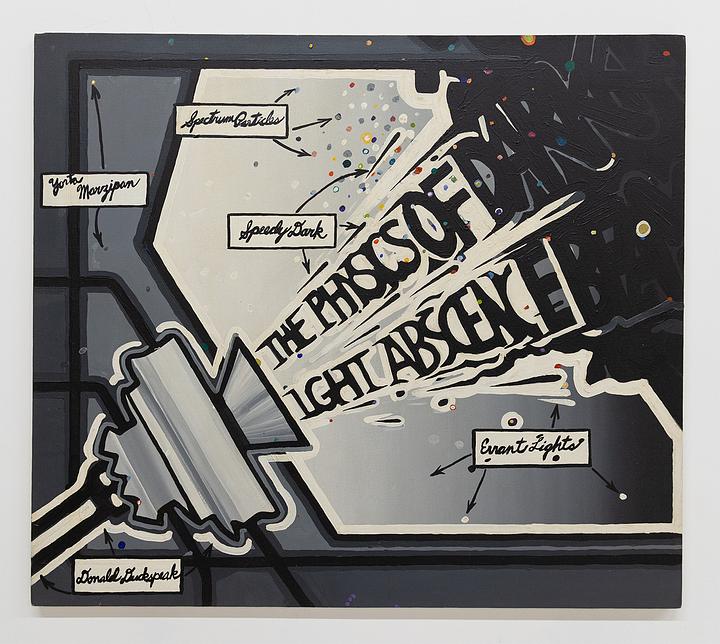

The Physics of Dark, 1969

Acrylic on canvas

35 x 39.75 in (88.9 x 101 cm)

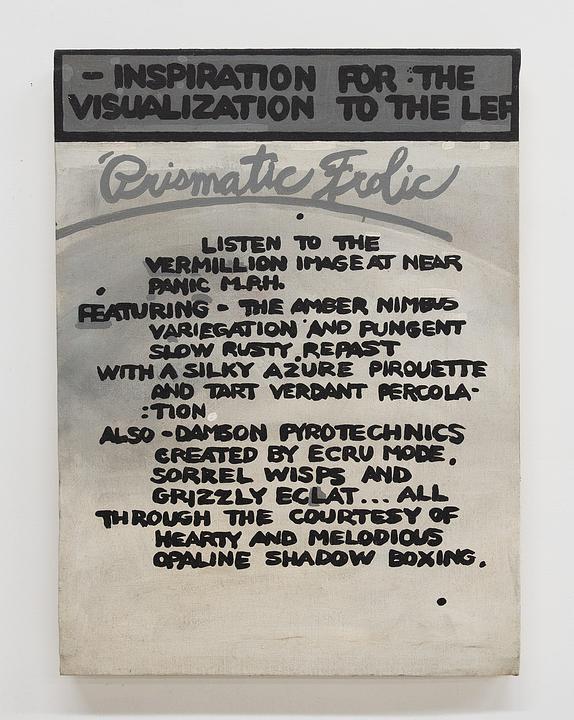

Prismatic Frolic, 1970s

Acrylic on canvas

23.5 x 17.5 in (59.7 x 44.5 cm)

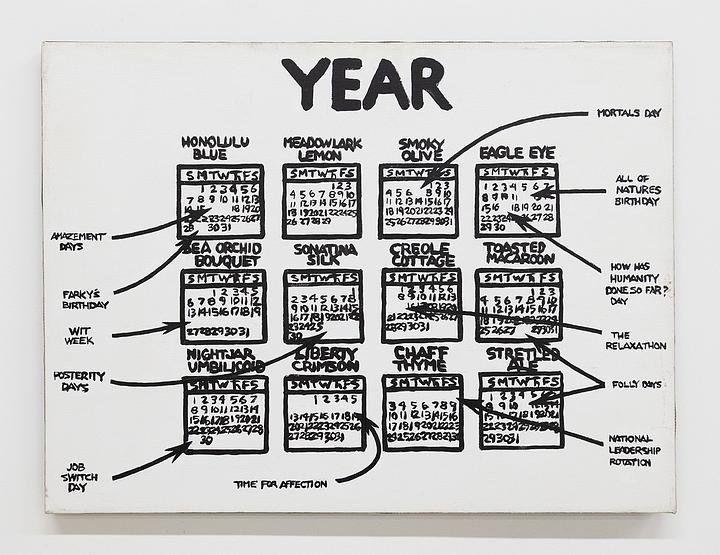

A Very Good Year!, 1996

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 24 in (45.7 x 61 cm)

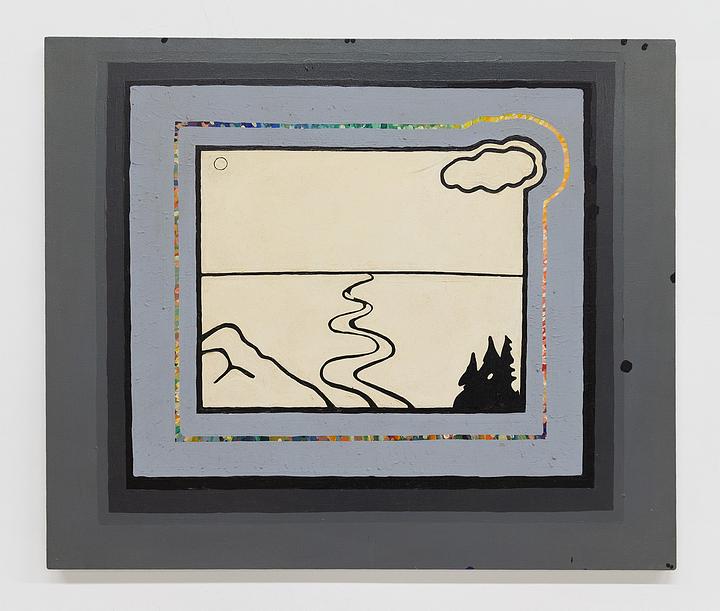

Untitled, 1970

Acrylic on canvas

32 x 38 in (81.3 x 96.5 cm)

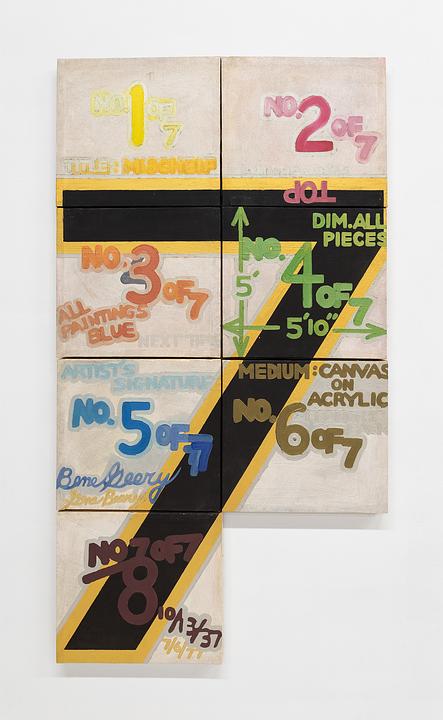

Mischief, 1973

Acrylic on canvas

62 x 34 in (159.4 x 86 cm)

7 panels each measuring 15 x 16.5 in (38.1 x 41.9 cm)

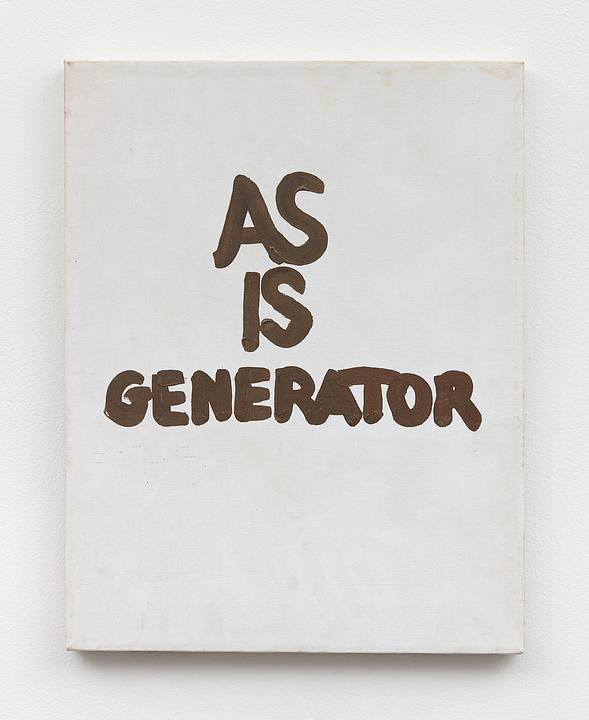

As Is Generator, 2007

Acrylic on canvas

20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

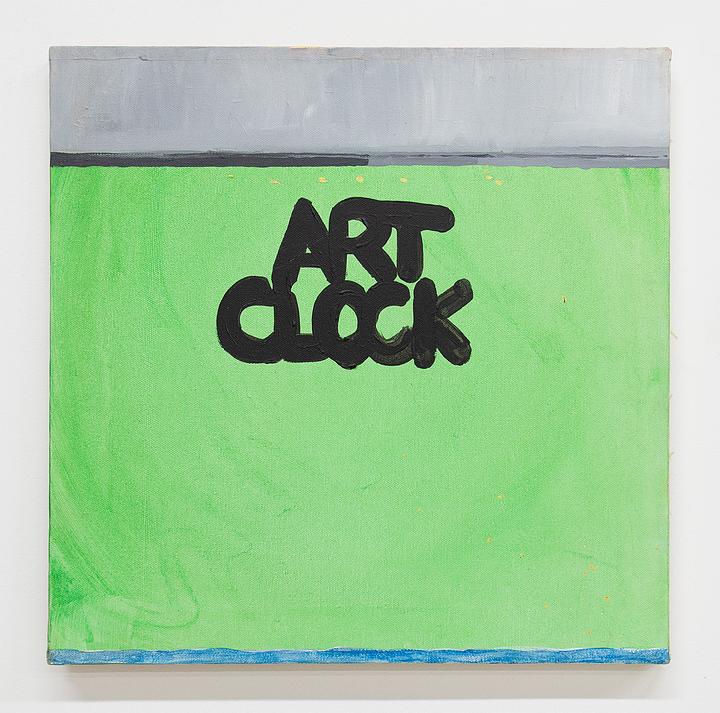

Art Clock, 1993

Acrylic on canvas

16 x 16 in (40.6 x 40.6 cm)

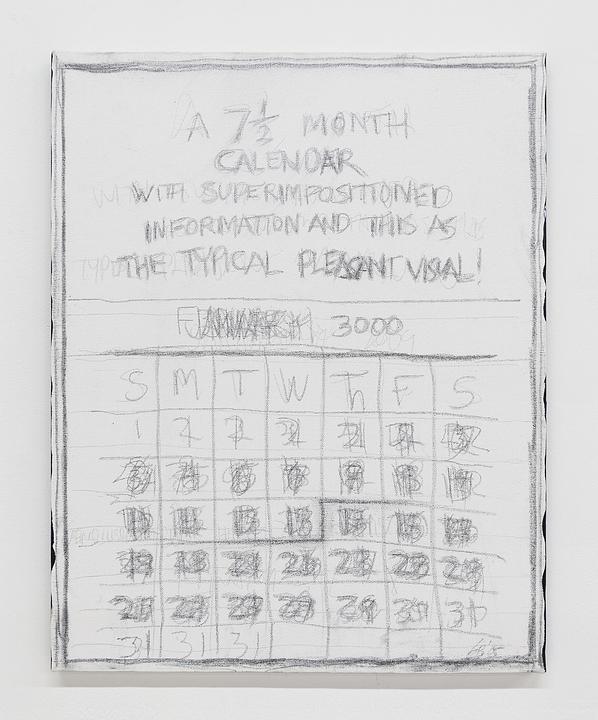

A 7½ Month Calendar, 2005

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

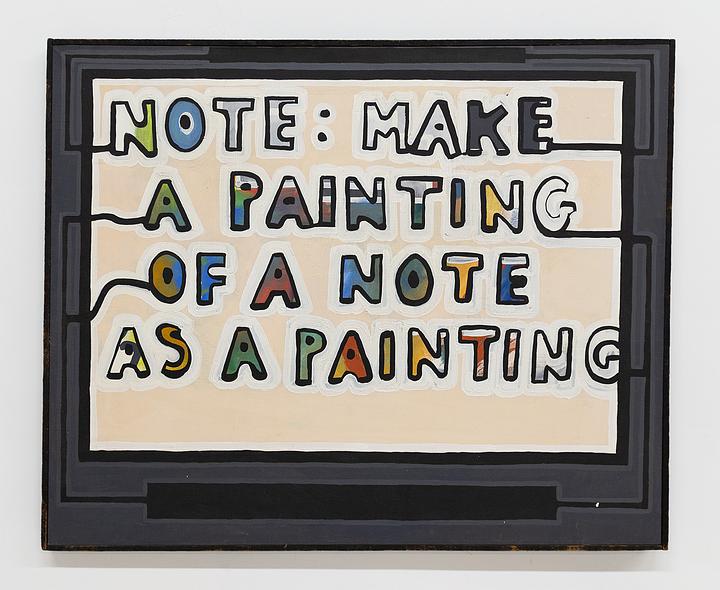

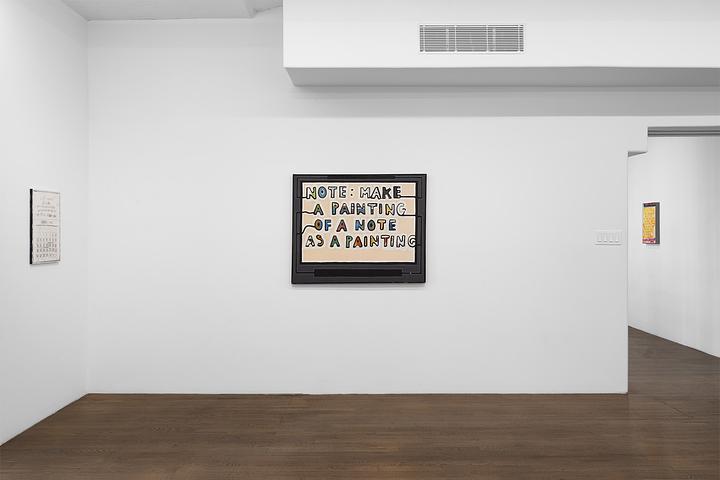

Note, 1970

Acrylic on canvas

34 x 42 in (86.4 x 106.7 cm)

The Time Binder, 1990s

Acrylic on canvas

19.5 x 25.5 in (49.5 x 64.8 cm)

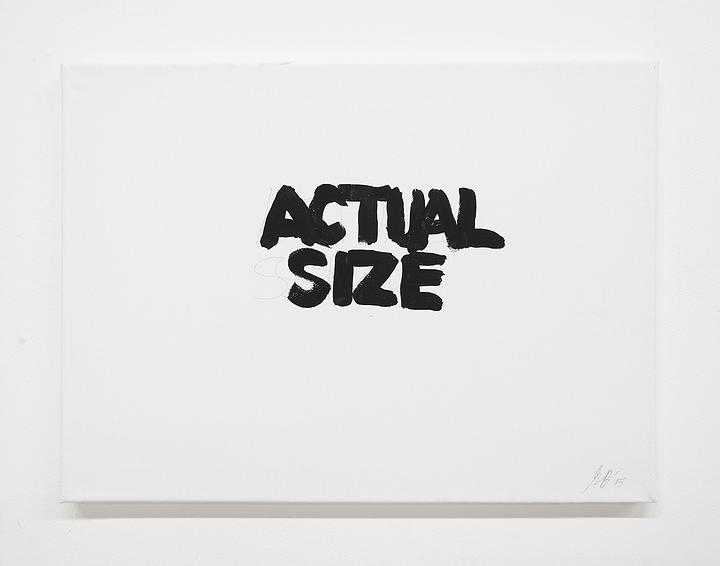

Actual Size, 2015

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

16 x 12 in (40.6 x 30.5 cm)

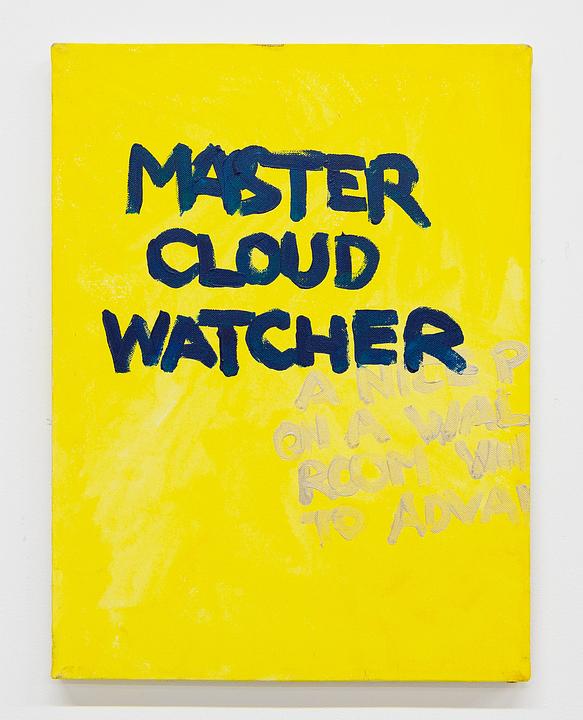

Master Cloud Watcher, 1990

Acrylic on canvas

16 x 12 in (40.6 x 30.5 cm)

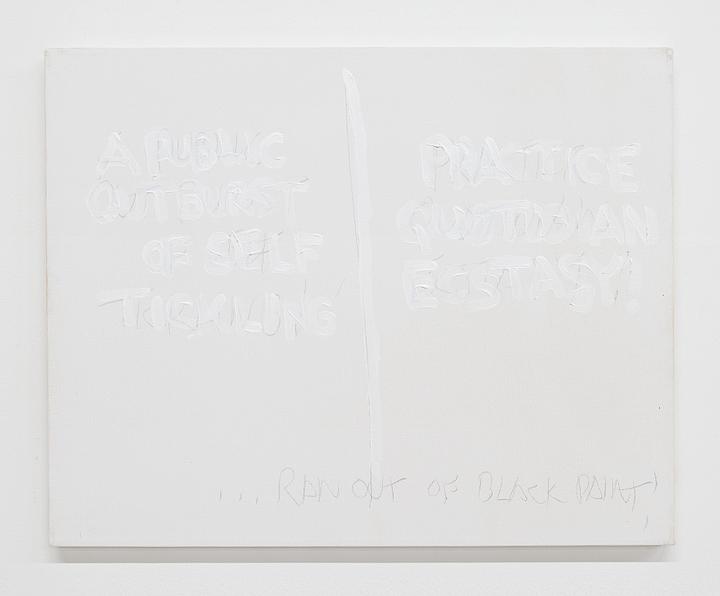

Out of Black Paint, 2000s

Acrylic on canvas

16 x 20 in (40.6 x 50.8 cm)

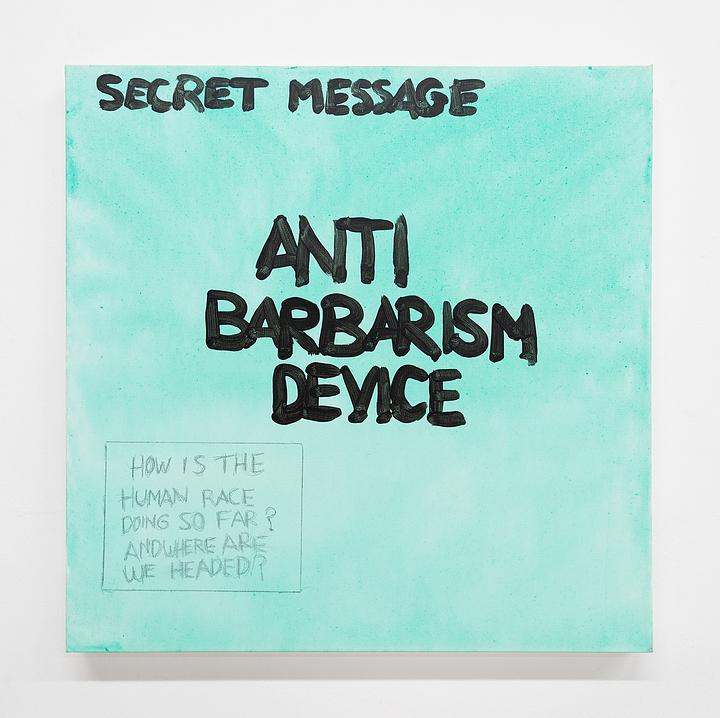

Anti Barbarism Device, 2010

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

24 x 24 in (61 x 61 cm)

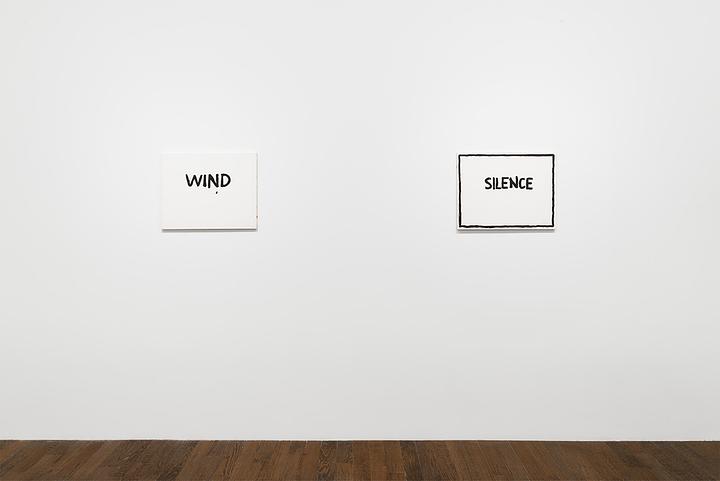

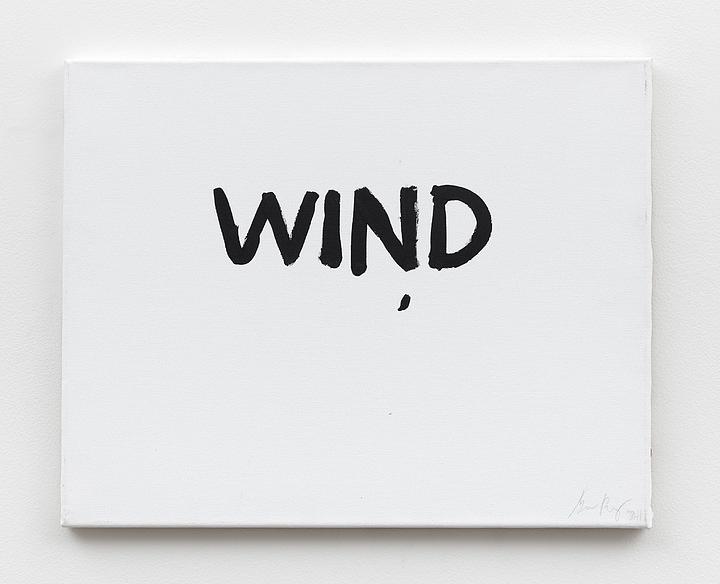

Wind, 2011

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

16 x 20 in (40.6 x 50.8 cm)

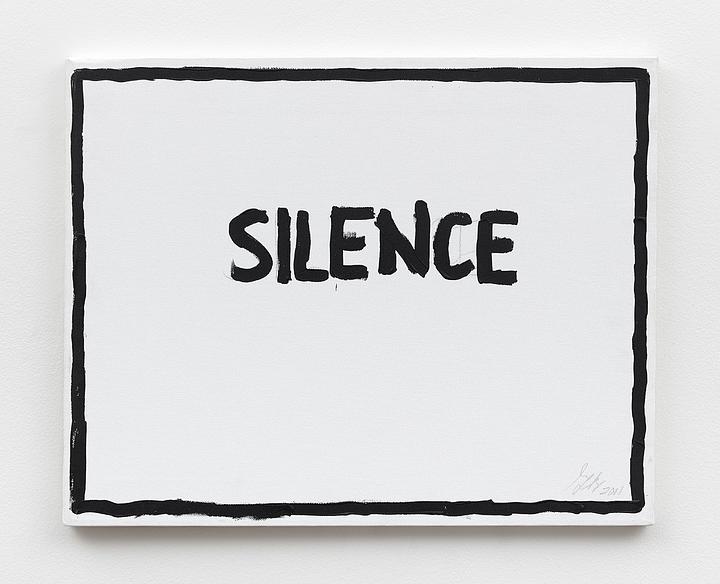

Silence, 2011

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

16 x 20 in (40.6 x 50.8 cm)

This exhibition focuses on Gene Beery’s explorations of time, seriality, and numbers, in works spanning from 1969 to 2015. Such topics might initially conjure the solemn austerity of many conceptual artworks from his generation. But all throughout his career, Beery thumbed his nose at art’s self-serious mores and expectations, infusing biography, color, gesture, and above all, humor into the gray schematics of programmatic conceptualism. In his work, time might appear as an existential profundity, but more often it appears as the passing of the everyday (‘killing time’); seriality might manifest in “rigorous governing logics,” but it is more often humble, like how people in line at the post office add up to a “series” just by standing in a certain order. Numbers show up not in the sense of computation or finance, but in the sense of counting on your fingers.

Subversions like these deflate art and bring it down to Earth. Once it has landed, Beery shows how transcendence still happens at ground level: to “Practice Quotidian Ecstasy” is to access higher planes through practical means, with what’s in front of you. Quotidian ecstasy can be found in weather, in nature, in moments of silence, in things just as they are: in the everyday miracle of life.

Mel Bochner, in a key text of Conceptual Art, aligns serial art and systems with “solipsism”: it is “self-contained and non-referential,” and so extends the high-modernist value of autonomy into the realm of information.¹ Beery does not appear in Bochner’s list of Conceptualists (though it’s not unthinkable that he could have, in some other timeline: he was friends and interlocutors with Bochner’s key example, Sol LeWitt, and he contributed to several of Lucy Lippard’s “Numbers” exhibitions). Perhaps one reason is because Beery, clearly, insists on non-autonomy; he refuses to refuse the world. His paintings are not only referential to the world, but operative within it. With him, paintings act: as diary, as calendar, as note-to-self; as “Clock,” as “Generator,” as “Device.”

One remarkable work in this exhibition, titled Mischief (1973), might be said to operate as a laundry list for the bits of information that make up an authentic, authenticated artwork. Made of seven panels in an asymmetric grid (put together, they spell out a composite “7”), the work assigns a different aspect to each of the seven canvases: title, orientation, formal description (“all paintings blue”), dimensions, artist’s signature, medium, and date. Together, they add up to something like the information of a checklist entry—which is one way of saying they add up to an artwork. The last panel, for date, actually lists two dates: October 13, 1937, which is foregrounded, and July 6, 1977, which sits behind the first. The first is the artist’s date of birth, and the second, one might assume to be the date of the work’s completion—but it is in fact from four years earlier. Whatever the forecasted date might mean, between it and the first lie 14,511 days: 39 years, 8 months, and 24 days on Earth, along which this painting was made. Life into art, art into life: Gene lived another 16,938 days, up to his passing last November. That’s 31,449 days total.

Life is short, but it can also be long. In any case, there’s lots to see and do along the way. How many miracles pass right before our eyes?

—Nick Irvin

Gene Beery (b. 1937, Racine, WI; d. 2023, Sutter Creek, CA). The artist’s first retrospective was organized by Balthazar Lovay at Fri Art Kunsthalle, Fribourg, Switzerland in 2019. Recent solo exhibitions include those held at Parker Gallery (2022), Derosia, New York (2020), Cushion Works, San Francisco (2019), Shoot the Lobster, Los Angeles, CA (2017) and Jan Kaps, Cologne, Germany (2016). Recent institutional group exhibitions include Rules & Repetition, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT (2023); AOULIOULE, curated by Sylvie Fanchon and Camila Oliveira Fairclough, Musée régional d’art contemporain Occitanie, Serignan, France (2022); The Drawing Centre Show, curated by Franck Gautherot, Seungduk Kim, Tobias Pils and Joe Bradley, Le Consortium, Dijon, France (2022); and Stop Painting, organized by Peter Fischli, Fondazione Prada, Venice, Italy (2021). The artist’s work has also been included in historical group presentations, including the 1975 Biennial Exhibition, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (1975); and 955,000, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada (1970) and 557,087, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA (1969), both curated by Lucy Lippard.

___________________________________

¹ Mel Bochner, “Serial Art, Systems, Solipsism,” in Solar System & Rest Rooms: Writings and Interviews, 1965-2007 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 92-102. Originally published in Arts Magazine, Summer 1967.