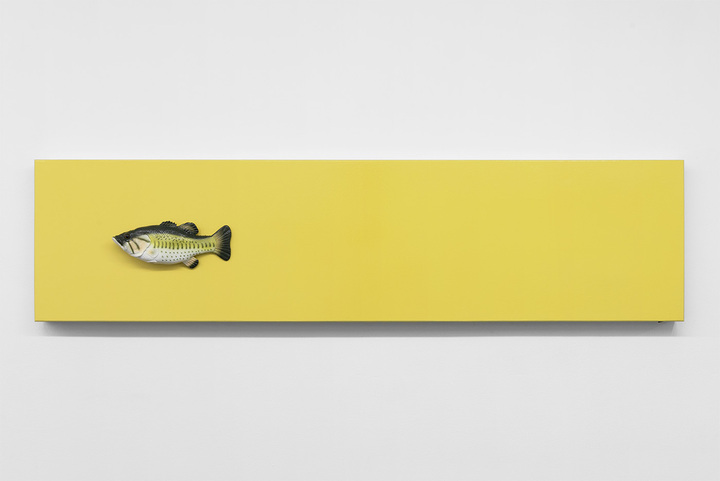

Seeker, 2020

Audio, wood, enamel, Big Mouth Billy Bass

24 x 72 x 5.5 in (61 x 182.9 x 14 cm)

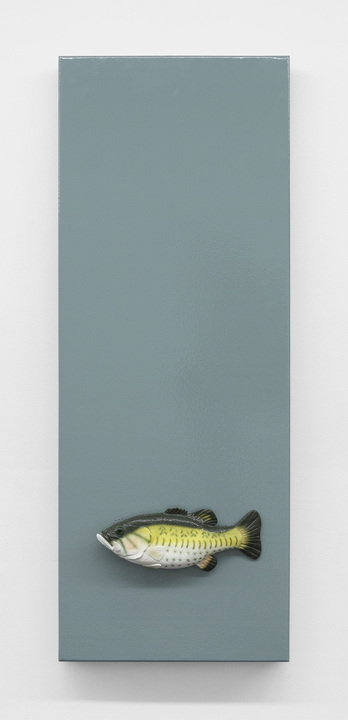

Pleader, 2020

Audio, wood, enamel, Big Mouth Billy Bass

48 x 24 x 5.5 in (121.9 x 61 x 14 cm)

Chum, 2020

Audio, wood, enamel, Big Mouth Billy Bass

48 x 24 x 5.5 in (121.9 x 61 x 14 cm)

Pitcher, 2020

Audio, wood, enamel, Big Mouth Billy Bass

48 x 24 x 5.5 in (121.9 x 61 x 14 cm)

Trawler, 2020

Audio, wood, enamel, Big Mouth Billy Bass

30 x 27.5 x 5.5 in (76.2 x 69.9 x 14 cm)

Remember Big Mouth Billy Bass? Exhume him from the man-cave in the basement of your memory, out from a box with some Big Dog shirts and a PC tower that, if you were to boot it up, still has “Frog in a Blender” set as its only bookmark. We’re in the domain of the Uncle. Not quite of the Father, who, despite everything and however nominally, still assumes the mantle of law and order. The Uncle, instead, is free-floating: he holds all the entitlement and threat of the patriarch, with none of the obligations. If Father is Tragedy, then Uncle is Farce: he’s not a banker, but an RV dealer; not a fisherman, but still an Ahab of sorts, if only in the Rite Aid clearance section. It’s telling that America fell in love with this fish when it did, on the eve of the twenty-first century.

Before he became nationally recognizable, Billy Bass was meant to surprise you. The first generation Bass was activated by motion sensor, the idea being that this innocuous kitsch-decor would come to life for unsuspecting passersby. The taxidermied prey peels off the wall and confronts the surveilled, an eerie reanimation set to the tune of either “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” or “Take Me to the River.” Later versions replaced the motion sensor with a simple button, softening his song’s affront. But then you have your Uncle pressing it every thirty minutes to impress everyone at the family reunion.

This initial threat factor of Billy Bass—his sense of knowing—is preserved in his appearances throughout Season 3 of The Sopranos, where the fish functions as a cursed memento mori, half Yorick’s skull and half Tell-Tale Heart. Whether it’s Christopher assuming that Paulie is pulling a gun on him when in fact it’s just the Bass, or Tony being triggered by the fish’s accusatory gaze and bashing it over the head of the poor bartender, or Meadow gifting yet another fish to Tony the following Christmas, unaware of the terror it brings to her father, The Sopranos identifies some trauma lurking beneath the surface of Billy Bass’s camp. It seems to have something to do with the awkward pain of intergenerational disconnect—the moment when the Uncle’s joke misfires.

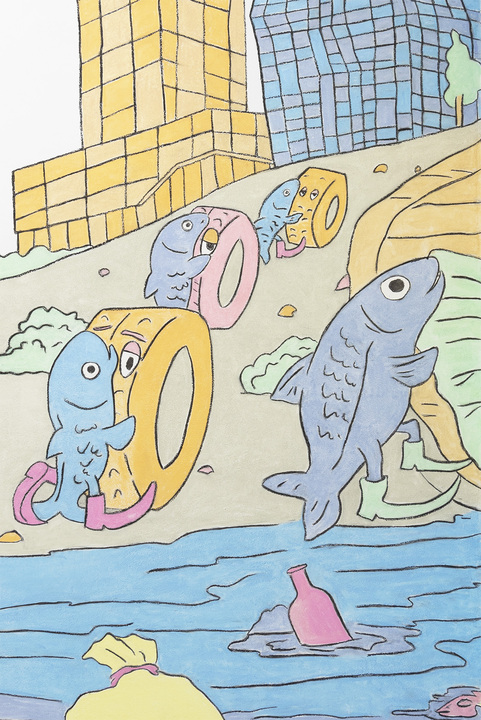

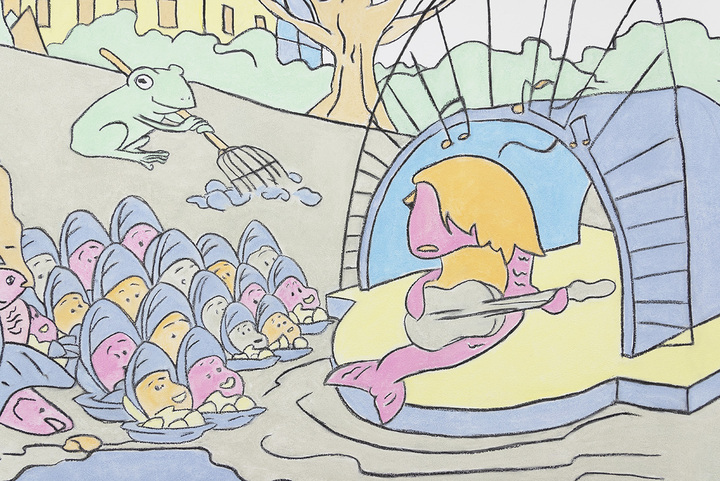

What else do fish know? In this exhibition, Dena brings in a bit of ancient folk wisdom with a mural that riffs on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s dystopic tableau, “Big Fish Eat Little Fish,” drawn in 1556 and distributed as an engraving in 1557. A boatsman recounts to his son a Latin proverb, which has manifested before them with grotesque literality: “Look, son, I have long known that the big fish eat the small.” The scene is replete with fish within fish; most fish are eating others, while themselves being eaten. A coastal trade city gleams on the horizon. Do you see where Bruegel is going with this? Dena recasts the scene for our own times and our own imperial capital, where exploitation and predation have taken on dimensions that an early modern Dutch fishmonger could never have fathomed.

On the mural’s right, an emo fish sings a song on the East River Park Amphitheater’s stage—an early Robert Moses construction, and so a symbol of a past era’s paternalism, conceived by one of that era’s most hated Fathers. And yet it’s beloved, too, and now endangered: the city plans to demolish it this fall, along with the rest of the park, to fortify the Lower East Side against rising sea levels. Eventually, they will top the new landfill with new landscaping, designed to be more in step with the taste of contemporary real estate developers (the ultimate Uncles). This, though, was preceded by a more modest demolition of half the original structure in 2002, as part of Giuliani’s post-9/11 downtown “rehab” campaign. The big fish comes even for Moses, and then a bigger one still…

Meanwhile, Dena has staged a performance of five Billy Basses talking past each other, each trying to get a grip in our sinking city. Each portraying an archetype, they stumble through something like a group therapy session, straining to connect from their respective mounts despite the imporosity of each’s worldview. There’s at least one thing they have in common: they’re thirsty.

—Nick Irvin

Dena Yago (b. 1988, New York, NY) lives and works in New York City.

Recent solo exhibitions include High Art, Paris; Atlanta Contemporary, Atlanta; Bodega, New York; Sandy Brown, Berlin; and Boatos Fine Art, Sao Paulo. Recent group exhibitions include Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, The Netherlands; Kunsthal Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark; The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; The Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw; Watermill Center, Watermill, NY; Emalin, London; Bortolami, New York, NY; and Park View/Paul Soto, Los Angeles.

Her work has been reviewed in The New York Times, Frieze, Artforum, Art in America, Flash Art, Mousse Magazine, CURA Magazine, Garage Magazine, Bomb, and DIS Magazine, among others.

Yago has published numerous texts including "The Walls Stays in the Picture: Destination Murals in Los Angeles" (e-flux journal, 2019); "Soft Serve: On Food, Affect, and the Silicon Valley Workplace" (Frieze, 2019); "Content Industrial Complex" (e-flux journal, 2019); "Bad Memory" (Flash Art, 2017); "On Ketamine and Added Value" (e-flux, 2017); and "Empire Poetry" (Texte zur Kunst, 2016). Multiple books of her work have been published including Fade the Lure (After 8 Books, 2019); Esprit Reprise (Pork Salad Press, 2015); and Ambergris (Bodega Press, 2014).

Her work is included in the permanent collection of The Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, The Netherlands.

This is Yago’s second solo exhibition at the gallery.